Local rumor has it that the Emma Silver Mine in Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon almost started a war with England in the 1870s. Located near the Alta Ski Area (of 2002 Winter Olympics fame), the Emma Mine consists of a large tunnel bored into the granite rock face of a remote Utah canyon.

After miners tapped out the central silver vein, knowing full well that Emma Mine was empty, an American senator and businessman attempted to sell off their shares in the project to hapless British investors.

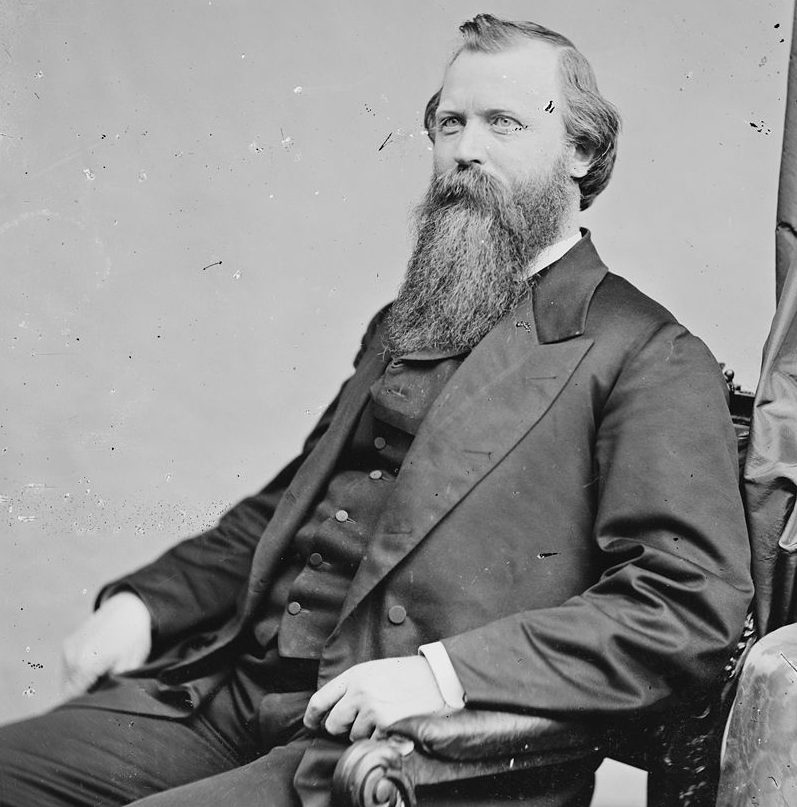

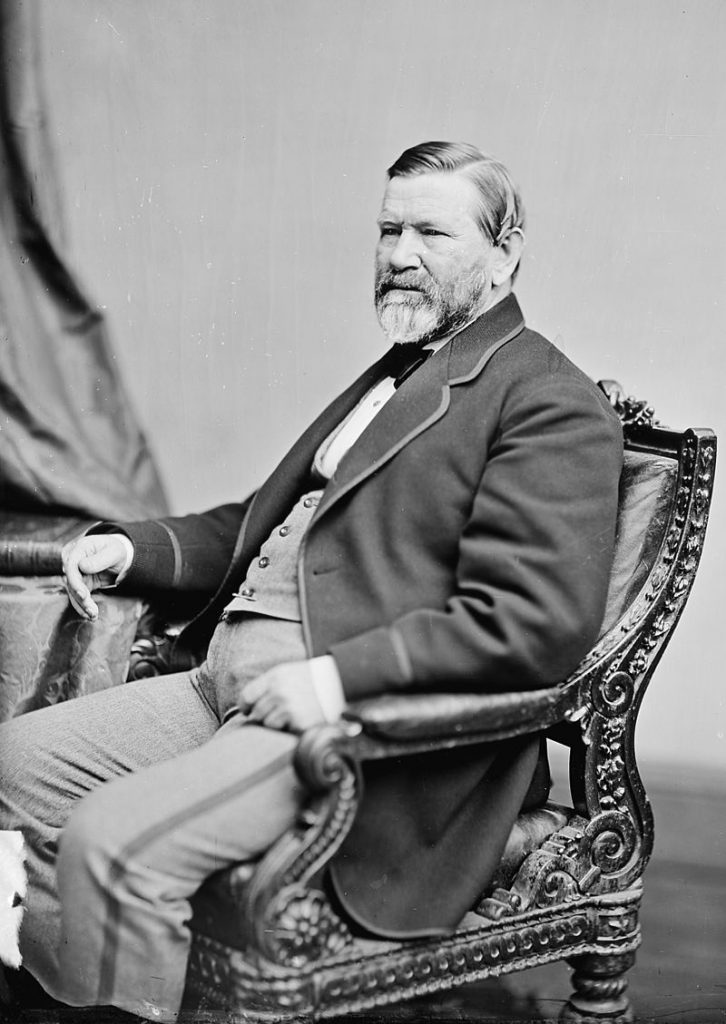

US Minister to England Robert C. Schenck, an Ohio Republican, partnered with Trenor W. Park, one of the mine’s owners, to organize the scheme. The mine’s other owners included James Lyon as well as Horace Henry Baxter, a New York business promoter and a Civil War hero from Vermont.

Park and Schenck allegedly paid Yale chemistry professor Benjamin Silliman some $50,000 to write a report claiming that the Emma Mine was “one of the great mines of the world” and had “great value.” The mine produced $2 million worth of silver in the summer of 1871. However, the site was an “accidental deposit, or ‘pocket,’ [and] was not a true fissure vein,” according to an 1876 article from The New York Times.

By the time Park and Schenck schemed to sell Emma Mine, there was very little silver left inside the cavern. Moreover, the site was already difficult to manage because of the large amount of water that had permeated the granite. In short, Schenck and Park knew they were never going to get more out of the lode, and selling the place was nothing short of a scam.

RELATED: Hiram Maxim – The Right Place, Right Time, Right Gun to Change History

Schenck and Park cut Lyon out of the sale of the mine. For his part, Lyon sued, claiming that Park and Schenck had bribed his lawyer, William Stewart — a Nevada senator — with stock from the defunct mine. In Lyon’s court case, Schenck and Park also conspired to use stocks to buy and sway the lawsuit’s jury.

Lyon likely lost his case in Utah because his lawyer, Stewart, later testified against Schenck and Park. Technically, the mine sale was legal, but Schenck and Park deliberately misrepresented the worth of the silver the site held.

Albert Grant, “one of the leading and most detested London financial wizards of the last half of the nineteenth century,” according to one source, promoted the sale of Emma Mine stock in the London financial markets. Although Grant sold off his stake in the mine, the worth of those shares plummeted to near zero once authorities revealed that the Emma Mine was depleted and, therefore, effectively worthless.

RELATED: Photos – What Old West Life Was Really Like in Tombstone, Arizona

Ruffled by the potential geopolitical consequences, Congress conducted an inquiry into the matter. Because of their parts in the scandal, Schenck and Stewart became public pariahs. Stewart was already infamous — because of his extensive mine ownership throughout the West, his nickname was the “silver senator.” Thus, Stewart did not seek reelection after the Emma Mine affair became public, and he tendered his resignation to President Ulysses S. Grant.

London was severely displeased by the whole incident and threatened an investigation. Consequently, rumors began to spread that the scandal could spark an armed conflict. In any case, British threats to sue the US on behalf of the duped Emma Mine shareholders never materialized. Ultimately, the scandal only amounted to a war of words — and a historic embarrassment for the United States.

Today, the Emma Mine site’s only useful purpose is to provide the nearby city of Alta with a reliable source of fresh water.

Read Next: Oliver Winchester and Sam Colt – Innovators and Lousy Gunmakers

Comments