Our reliance on technology isn’t going away anytime soon. We have cellphones, satellite phones, GPS communicators, and GPS beacons that relay our locations to those with a need to know. What happens when technology fails? In US Army small-unit tactics, leaders use a five-point contingency plan any time they are separating from any portion of their unit. This plan is the ultimate backup for when technology fails and they lose communication with the members of the team they are separated from.

This five-point contingency planning isn’t only useful during military operations; it can be useful to those who frequently venture off the grid. Whether hunting, fishing, backpacking, skiing, or off-roading, briefing someone on your five-point contingency plan can save your life and lessen rescue times if you get in trouble in the wilderness.

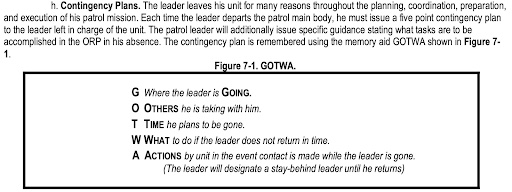

GOTWA: The acronym the troops use to remember the plan

I have used five-point contingency plans or modified versions of them for ski trips at resorts where there is no cell service. I have also used them in the field when separating from my hunting partners for the day. A well-constructed five-point plan will give your friends or loved ones a clear plan of action to take based on certain criteria. Let’s take a look at the scenario below to better understand how to formulate and brief a five-point.

Scenario 1

You are heading out on a six-day mule deer hunt in the Bob Marshall Wilderness of Montana in September. You have all the necessary gear, including a Garmin InReach GPS communicator; there is no cell service where you intend to hunt. You are leaving your wife and children at home and going solo. Using the acronym GOTWA, you will brief your wife on your plan.

G — Where You’re Going

I am driving to this trailhead to park (mark it on the Google Maps or similar app of the person you are telling). From that trailhead, I will hike 2.5 miles in and will look to set up camp in this vicinity (again, mark on a map where you plan to start and stop). Once I find a suitable camping spot, I will message you the location of my camp via InReach.

O — Others Going With You

If you have hunting partners going with you, this is where you will brief the person you are telling about who will be with you. In this case, you’re going solo, so no one.

T — Time You Will Be Gone

I will be home on the evening of Sept. 6. If I kill a deer on the last day, I will message you via InReach to inform you I’ll be late.

W — What To Do If You Do Not Return

If I am not home by 1800 on Sept. 6, call my cell and message my InReach. Wait three hours for a response. If I do not respond in three hours, initiate search and rescue. Brief the search and rescue team on my last known location from my InReach messages as well as the trailhead where my truck is parked.

“A” usually stands for “Actions on Contact” so that leaders and the element they leave behind have a clear plan of action if they’re engaged by the enemy during their separation. For our purposes, we will use “Final Plan of Action.”

A — Final Plan of Action

I will send you a message via InReach once each morning and evening. In my messages I will update this plan based on current circumstances. For example, if my battery chargers are dead and my InReach will die before I return home, I will send you an adjusted five-point plan. If, while I’m gone, you have not heard from me in 36 consecutive hours and I did not give you any additional instructions or update the five-point, message me one more time, wait one additional hour, then initiate search and rescue if I do not respond.

Remember, the purpose of a five-point plan is to have a contingency to fall back on if/when technology fails. Be sure to incorporate whatever technology you have into the plan along with what to do if that technology fails. You want to be as specific as possible and ensure that you address all of the “what ifs” that could come up while you’re afield.

In the above plan, if you fall off a cliff and break your leg and cannot reach your GPS communicator, using a timeline like 36 hours with no communication will initiate search and rescue. Without it, your loved ones might wait up to 24 hours after the day you’re supposed to return home to initiate search and rescue. That’s a long time to be stranded on the side of the mountain in pain.

Let’s look at another scenario.

Scenario 2

Marty, Mike, Logan, and Evan are going on a six-day backpack elk hunt in the Frank Church Wilderness of Idaho. Each has briefed their loved ones on individual five-point contingencies that also include the other three’s GPS communicator numbers so that if one communicator fails, the loved ones can contact another member of the hunting party for reassurance. Additionally, they have ensured that their respective loved ones being left at home all have each others’ numbers as another method of communication. Example: Marty and Logan forgot to pay their communicator bill, leaving Evan and Mike with the only working communicators. Evan and Mike’s loved ones can contact Marty and Logan’s loved ones each day to let them know all is well.

In this scenario, however, all parties have functioning communicators. After two days of not getting into elk, the hunters decide to separate into pairs to cover more ground in hopes of locating elk. Marty and Mike will go south of camp, and Logan and Evan will go east of camp to search for bugling bulls.

G — Where You’re Going

Marty and Mike: We are leaving camp and moving south. We intend to follow the ridge to the west of Disappointment Creek. We will follow this for 2 to 3 miles searching for sign and trying to locate elk.

Logan and Evan: We are leaving camp and moving east toward Hungry Creek. Once we reach Hungry Creek we will follow it north.

O — Others Going With You

In this case, no one is staying at camp and each party knows who is going with whom. If you were leaving someone at camp, or if one party was staying at camp, you would brief everyone on this. The “others going with you” step in GOTWA is for accountability, so everyone knows who and how many people went where if something goes wrong. In the event you need to initiate search and rescue, knowing exactly how many people are where and who they are will be key information for the SAR team.

T — Time You Will Be Gone

Both parties agree to meet back at camp no later than 2200.

W — What To Do If You Do Not Return

Marty and Mike: If we are not back by 2200 and you have not heard from us, wait until daylight and follow our proposed route. If you have not heard from us by 1200 the next day via InReach and have not found us, initiate search and rescue.

Logan and Evan: Same.

A — Final Plan of Action

Collective: If either group locates elk, we will message the other team and let them know. We will also adjust our five points accordingly. Both teams are prepared to bivvy camp with two days’ worth of food.

If we are going to be delayed in returning or move farther than we intended to, we will also adjust the plan. If both communication devices in one party die, we will move back to camp to meet the NLT (not later than) time (2200).

In this scenario, both teams have clear understandings of where each intends to go. They brief the general area they’re moving to using identifiable features on the map. This is important. Should something catastrophic happen to one of the teams, the team that initiates SAR can, at a minimum, give the SAR team a general area and feature on the map to start their search. If, when separating, Marty and Mike told the other team only that they were going south, SAR wouldn’t have much information for the search if they were to get into trouble. Once again, we have a host of technology at our disposal, and we want to incorporate it into our plan. But, ultimately, be prepared for it to fail.

During my 2019 elk hunting season, I backpacked 4 miles into the wilderness of Colorado. My longtime hunting partner was solo hunting about 20 miles away in the same unit. Back at my spike camp cooking dinner one evening, I received a message from my wife: “Have heard from Josh? His wife texted me she hasn’t heard from him in quite a while.” My heart sank, and all of the “what ifs” started going through my head. I decided to remain in place for the evening and hike out during daylight to go search for him. The next morning came, and I was packing up to hike out. By this time his wife was ready to initiate SAR. Luckily, he finally came up on comms, and all was well.

In this case, there was no clear plan left with his wife for what to do if she didn’t hear from him, which nearly caused the unnecessary deployment of valuable SAR assets. This could have been prevented by the use of a clear and concise five-point contingency plan. Luckily, no assets were wasted and everyone was safe.

If you like to participate in high-risk activities and venture off the beaten path, following this outline could save your life. Regardless of how well you know the mountain you’re skiing, area you’re hunting, or trail you’re hiking, leaving someone with a clear, concise plan for what to do can either save resources or initiate life-saving SAR in the event you get into trouble. Before your next trip, take some time to work up a clear plan of action using GOTWA, letting your loved ones know what to do and when they should do it.

Read Next: 5 Winter Survival Tips You Need To Know, According to the Boy Scouts

Comments