Carl Akeley had never been to Africa. Daniel Elliot, one of Akeley’s mentors and the curator for the zoology department of the Field Columbian Museum in Chicago, invited the 32-year-old in 1896 on an eight-month expedition to Somaliland. Akeley jumped at the opportunity.

On a hunt they spotted an animal in the tall grass. Akeley thought it was a warthog and wanted it for his collection. He aimed fast, and fired. He missed his target and then through his rifle sights he realized that was no warthog at all.

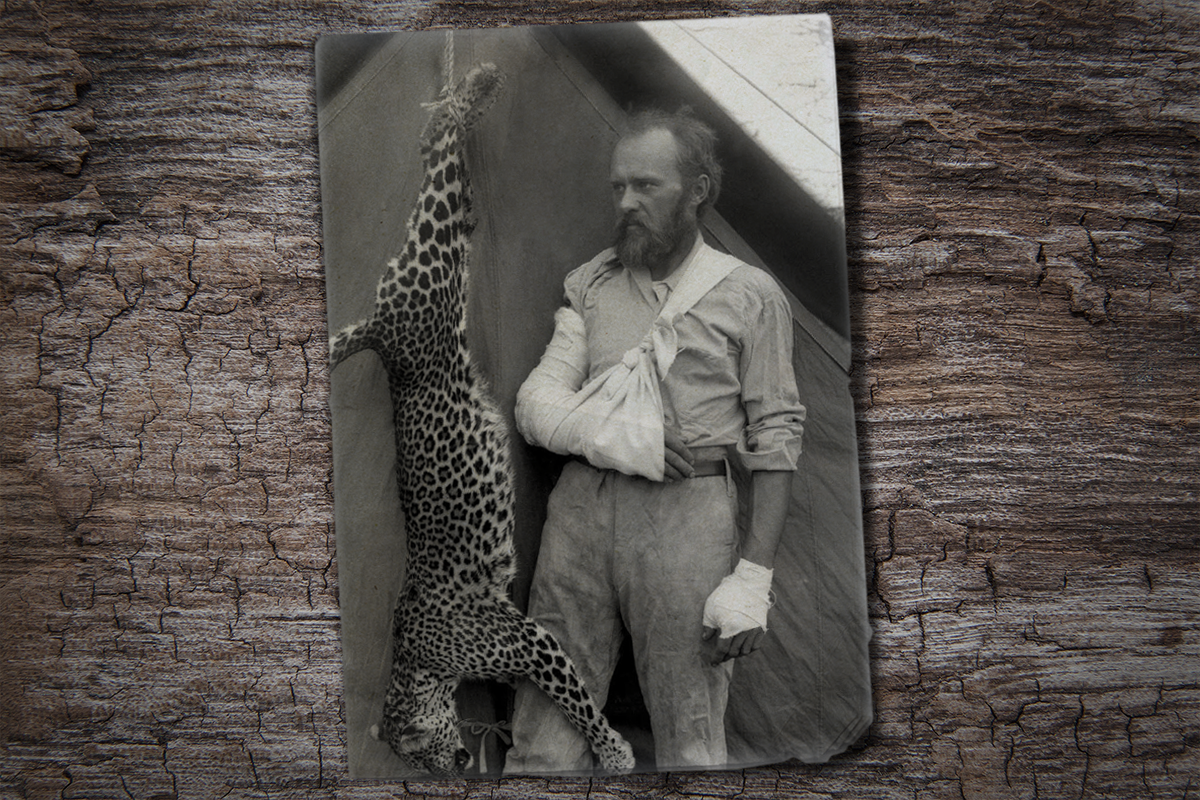

The leopard charged him. Akeley fired three more times and grazed the young leopard in its back leg with the third shot. He hurried to reload, only to realize he was out of ammo.

He tried to run, but the cat pounced. Akeley turned to face the leopard just as it connected with his head and chest. Akeley sunk his forearm into the animal’s jaws. During the struggle, Akeley forced his right arm down the throat of the leopard and used his left hand to strangle the beast. He choked the life out of the big cat, then battered and bleeding, threw it over his shoulder and made the walk back to camp. A revealing photograph taken later shows his right arm tightly wrapped in a sling, his left hand heavily bandaged. The cat hangs from a pole outside his tent.

The encounter with the leopard in the wildlands on the Horn of Africa left a memorable impression on the man who would later be dubbed “the father of modern taxidermy.”

Akeley was born in 1864 and grew up on a farm near Clarendon, New York. His fascination with the preservation of animals began when he was just 12 years old. Akeley was first exposed to the practice at an exhibit held in Rochester, New York, that showed 50 small mammals and birds. It was the work of David Bruce, a part-time taxidermist. After a friend’s canary died, Akeley asked if he could take it home and “fix” it, later sewing in glass beads for its eyes.

He taught himself his own techniques and later worked under Bruce when he turned 18. Bruce suggested that he should develop his skills as an apprentice under Professor Henry Ward, one of the most famous taxidermists in the country, at Ward’s Natural Science Establishment. He worked around the clock, from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m., sometimes spending the night to develop his techniques. On one occasion he fell asleep and his boss fired him for napping on the job.

Ward, however, forgave the young prodigy and requested his assistance for a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The task was stuffing Jumbo the Elephant from P.T. Barnum’s “The Greatest Show on Earth” fame. Jumbo was killed in a railroad accident in 1885 and Barnum requested not one, but two Jumbos, to be featured on display. It was a daunting undertaking, simply because of the size of the carcass itself. Jumbo’s skin weighed 1,500 pounds and his bones 2,400 pounds. The skeleton would be used for the first Jumbo, while Akeley supplemented the bones with bent wood and iron to support the second taxidermied hide.

Barnum toured the country with Jumbo for three years before he donated him to Tufts University in 1889. Barnum’s donation featured Jumbo as the centerpiece at the Barnum Museum of Natural History, where his prominence led to the school’s adopting him as its mascot.

Akeley’s friend William Morton Wheeler convinced him to take a job at the Milwaukee Public Museum in 1888. He felt he didn’t have the freedom to express his ideas and try out new techniques there, so after seven years, he accepted an offer from the Field Columbian Museum. It was here where he developed his revolutionary taxidermy style in which he posed animals to appear in a lifelike manner, as if they were in their natural habitats. His animal hides covered sculptured bodies made from tubes, wires, and cloth. Plaster and clay were added to provide definition to muscles and shape tendons. Akeley rose to the status of visionary for his remarkable animal dioramas.

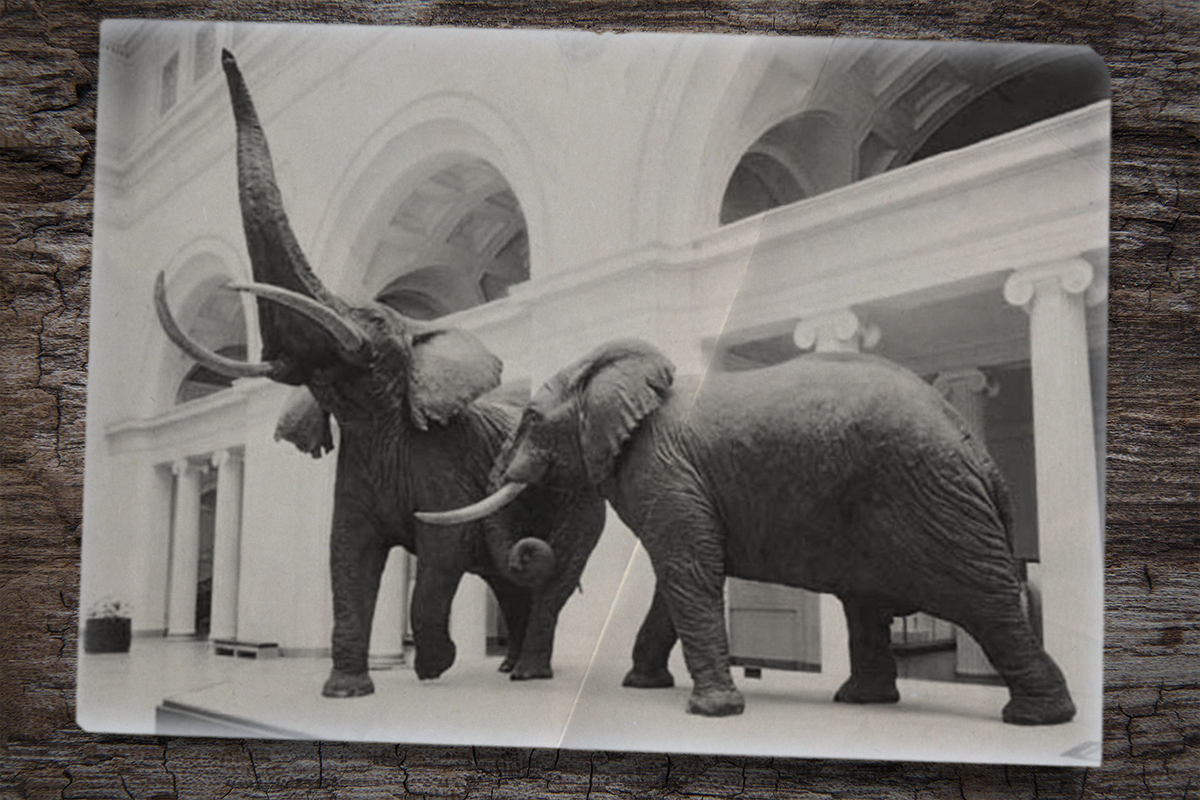

Once Akeley had recovered from his harrowing experience with the leopard he strangled, he went with his wife, Delia, on a second scouting trip to Africa. In 1905, they arrived in British East Africa, known today as the country of Kenya. The 12-month journey netted 17 tons of natural history material, including 400 mammal skins, 1,200 small mammal skins, 800 bird skins, and many mammal and bird skeletons. Among them were two bull elephants that were later modeled for display on the ground floor of the museum’s Stanley Field Hall.

Akeley would journey to Africa a handful of times between 1896 and 1926, including accompanying Theodore Roosevelt and his son, Kermit, on a voyage in 1909. In preparation, months prior to their survey, Akeley sent Roosevelt a model of an elephant head instead of drawings and photographs. He also crafted a camp table similar to the one he used on safaris and gave it to Roosevelt as a gift.

While in Africa, Roosevelt convinced Akeley he should commercially produce his invention of “shotcrete” — a plaster gun he had used only a few years before to repair a crumbling facade of the Field Museum in Chicago. The cement gun used compressed air to shoot concrete like a firehose shoots water.

When Akeley wasn’t on an expedition or mastering the art of taxidermy, he was writing books and sculpting African wildlife to present in realistic habitat dioramas. The Akeley Hall of African Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City is his magnum opus, the highest achievement of his life’s work. From black rhinoceros and ostriches to a watering-hole diorama that displays giraffes, a zebra, an oryx, a gazelle, a baboon, and herds of elephants, Akeley brings a distant world to within a few feet of each museum visitor.

The famed taxidermist and conservationist was studying mountain gorillas in the Congo in 1926 when he contracted a fever and died. He was 62 years old and is buried where he fell. It is because of a lifelong passion and the vision of Carl Akeley that exotic animals from Africa could be viewed in simulations of their natural habitats without being physically present in the wild.

Kent Marthaler says

In 1992, I purchased a massive moose head in Three Lakes, Wisconsin. Two(2) years later, I was contacted by the Seller who wanted to buy it back for three(3) times what I paid for it. He said it was one of the early heads done by Carl Ethan Ekeley when he worked @ the Field Museum of Chicago. How would know if this info is accurate & what should I do with it inasmuch as I am selling the house where the head hangs over a stone place in the living room? I have many pictures.

Mark says

for Kent — the only way to tell if Akeley mounted the head would be if he “signed” it or if the owner actually had documentation (maybe some records came to light 30 years later?). Akeley did no “side jobs” (that anyone knows of) while at the Field, but he did do hunting trophies at his private studio in Milwaukee between 1886 and 1895. If it’s his work, it’s more likely he did it during that period. He had his hands full after joining the Field in 1896. Would be interesting to see the proof.

Matt — buncha issues — no “tubes, wires, and cloth” inside his Field Museum mounts. From 1896 to 1902 it was a wooden armature, wire mesh, and plaster. From ~ 1902 (post “Four Seasons of the Virginia Deer” at the Field) it was hollow, wire mesh-reinforced papier-mache forms cast from plaster molds made from detailed sculptures. So, yes, clay in the original sculpture, but no clay in the manikins themselves. All that said, the work was exquisite and groundbreaking.

Akeley did not accompany the Roosevelts on their hunt, they joined HIM on his expedition for the AMNH, for a couple of days. And TR did not convince him to monetize the sprayable cement (then called “gunite” — the term “shotcrete,” a generic alternative for a “wet-mix” version was coined in 1951). Akeley filed two patents, in 1908 and 1909, before leaving for Africa, and signed a contract in early 1908 agreeing to share future royalties to the assistant who helped him invent the apparatus.

Finally, the AMNH Africa Hall was his magnificent vision, but not his magnum opus, because construction had not even started when he died in 1926. He had completed 4 elephants, and a temporary lion and gorilla group. Period. The rest of the hall, including the taxidermy, was completed by others 10 years after his death. His magnum opus is the Four Seasons at the Field Museum. No brag, just fact.