For decades, if someone drove north into Buffalo, New York, they would encounter an aerosolized wall of lingering pollution from the long-defunct Bethlehem Steel plant in the suburb of Lackawanna. The plant shuttered almost entirely in 1983, leaving over 10,000 people unemployed and the land declared a Superfund site. The loss of Bethlehem Steel was widely regarded among the local population as the nail in the coffin during Buffalo’s collapse as a longtime industrial driver for the state.

It took years for the city to regain its footing, but now the air has begun to clear.

Sarah Fonzi is a sculptor who helped start The Foundry, an organization in Buffalo that “aims to make our community more self-sustaining [and] provide workspace and tool access to artists and entrepreneurs.” Given the history and character of the city, she finds it “even more important to make art accessible.” In a fitting tribute to her hometown, Fonzi creates public art by pouring and welding metals.

Fonzi decided by fourth grade that she wanted to attend an art college. Despite working in many mediums as she grew up, everything always pointed her toward sculpture.

“I began making small sculptural collages around 3 years old,” she said.

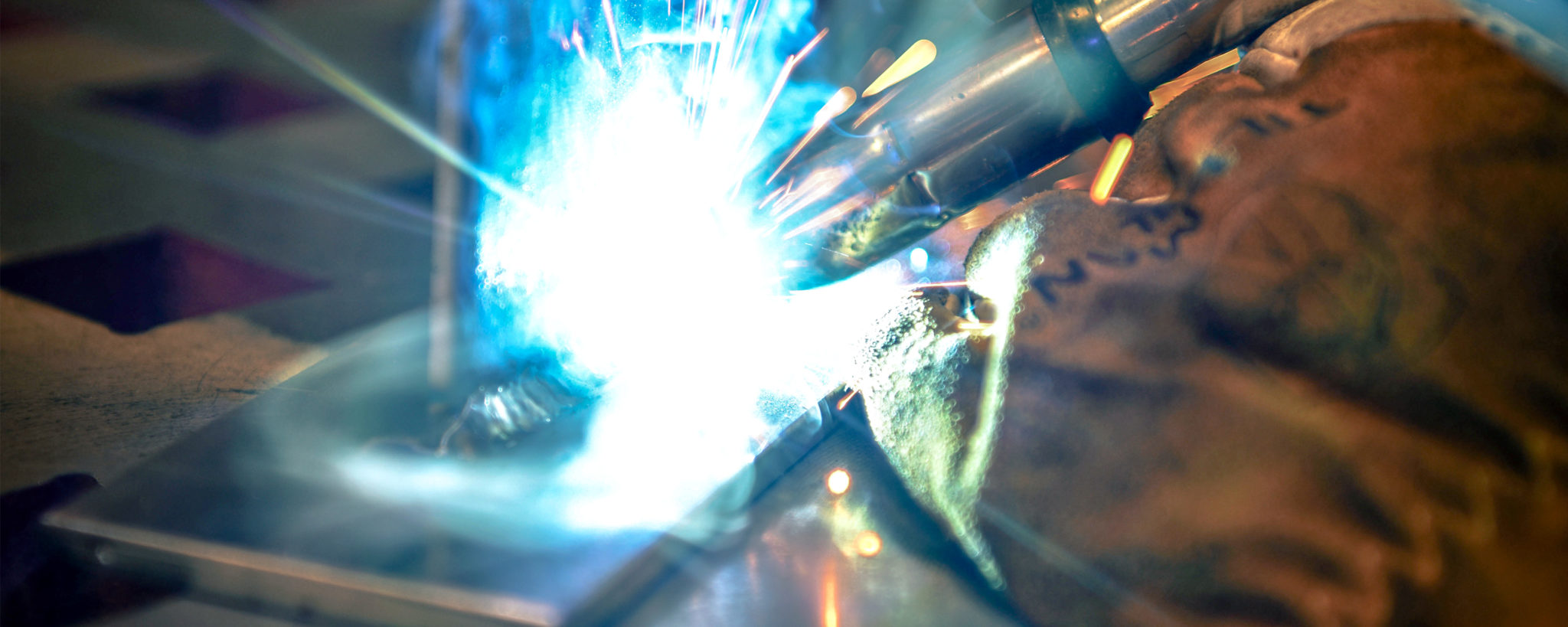

In school, she assumed she would work in a museum or gallery while doing woodwork as her personal art practice, but a summer in a welding sculpture course “rerouted my career.” Fonzi had to apply for a special dispensation to get into the course at the last minute, but it was worth it.

“That summer learning how to weld was incredibly empowering,” Fonzi says. “They were the most fun tools I had ever used, and it felt very natural and freeform.”

Despite her creative approach to welding techniques, she is fascinated by industrial welding as well.

“It is very exciting for me to watch and understand how welders operate on large buildings or bridges,” she said. “I may not be certified by the Department of Transportation, but I know how to do that. I always joke that if this art thing doesn’t work out, I’ll just go be a welder. It does give me relief knowing I am skilled in this way.”

Fonzi also worked with other media, including plaster, but she prefers working with metal.

“Pouring molten metal and welding it up into a sculpture is probably my favorite art practice. It is expensive, therefore I was looking for other media to fill that desire,” she said. “I have kept two studios, one for metalwork and another for plaster. One of the things that inspired my recent plaster casting is my love for metal casting.”

Fonzi is glad to have been able to contribute to Buffalo’s recent renaissance through her artwork.

“For many decades there has been a dearth of art in the public realm, and it is just now being addressed,” she said. “When people experience art in their daily life, their world expands and contracts. Ideas are formed, imagination evolves, their brain function and understanding of the world is strengthened.”

One of Fonzi’s most prominent works of public art is “Spirit of Transportation,” a piece showcasing the increase in bicycle travel in a city that struggled to create a workable public transportation system in the 1970s. Commissioned by the Buffalo Renaissance Foundation, it is crafted in stainless steel.

“They were looking for a sculpture to commemorate the history of the bicycle,” Fonzi said. “The bike grows out of a tall, tree-like structure, speaking to the growth and sustainability derived from the creation and availability of bicycles.” It is displayed in front of the Hub, a mixed-use development in a newly revitalized part of downtown Buffalo.

Helping to beautify a city coming back from such a long decline has been very satisfying. Fonzi said that the new construction in the city has resulted in more requests from developers and business owners.

Like so many places across the country, changes in the industrial economy deeply affected the city. With a population exceeding 1 million, Buffalo is the second-largest metropolitan area in New York State, but its population has taken a nosedive since its peak days in the mid-20th century. Between new transportation routes that rendered the once-bustling Erie Canal largely obsolete and the decline of its industrial base, the city proper has less than half the population it did in the 1950 census; 2017 numbers put it at 211,758 residents.

But organizations like The Foundry are in line with other recent revitalization projects in the city. PUSH Buffalo buys devalued housing stock and transforms entire depressed neighborhoods into newly burnished yet still affordable gems. And the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation’s Canalside development has taken a depressed waterfront area and turned it into a bustling hub of commerce and entertainment.

The Foundry is not simply a place for artists to reutilize old workspaces to create new work. It is also a center of activity for the community, exposing people to forms of art, such as metalwork, that they might never have considered pursuing before.

The confluence of art and industry is made explicit in Fonzi’s welding classes. “Buffalo has a huge need for welders right now,” Fonzi said, “so we are actively engaging with youth and young adults to introduce them to these career possibilities.” The need for skilled trades is not isolated to Buffalo alone; the nation as a whole is experiencing the same epidemic with most young people shying away from these professions in favor of the traditional university route.

The Foundry specifically “provides opportunities for youth to learn a trade and understand what entrepreneurship looks like.” Fonzi is a founder and sits on the board of directors.

Fonzi is a lifelong resident of Buffalo and her work, both her art and outreach, reflects that lifetime of exposure.

“Public art is so important for every community but certainly Buffalo,” she said.

While Buffalo redefines itself, though, the creativity of people like Sarah Fonzi helps maintain a connection to the culture of the past. For a historically blue-collar city, it is imperative that moving forward doesn’t mean forgetting where it has been.

This article was originally published Dec. 19, 2019, on Coffee or Die.

Read Next: Historic Hikes: 4 Must-Visit Trails for History Buffs

Comments