Everyone knows about the Boston Tea Party, right? King George III of England levied yet another tax on the American colonists, this time on the most basic and necessary commodity of tea. It was the last act before the kettle of revolution began to boil over.

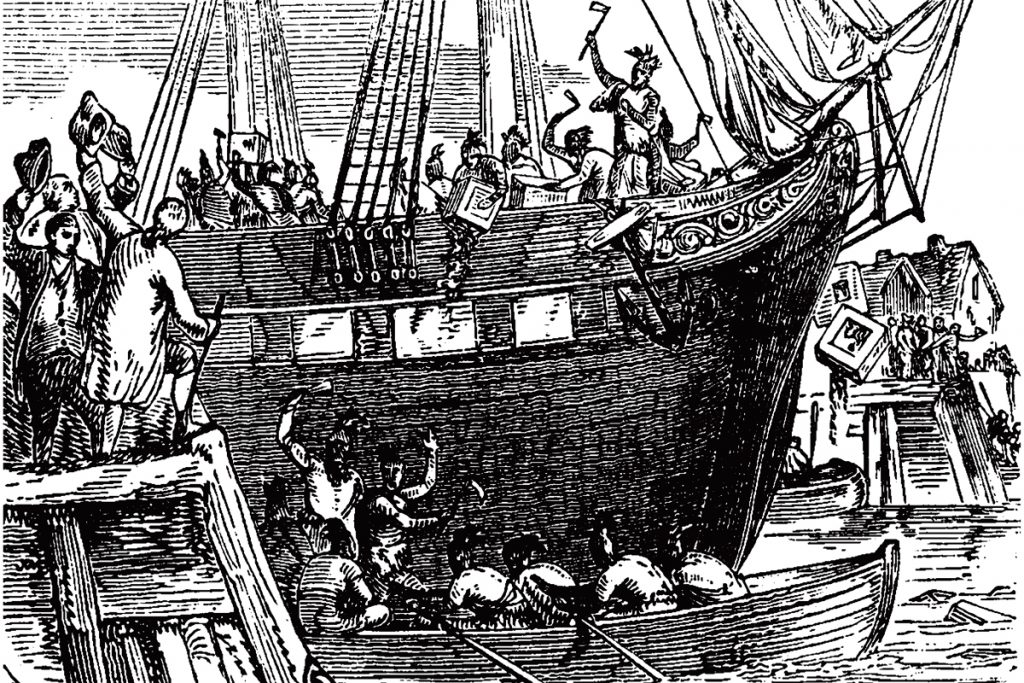

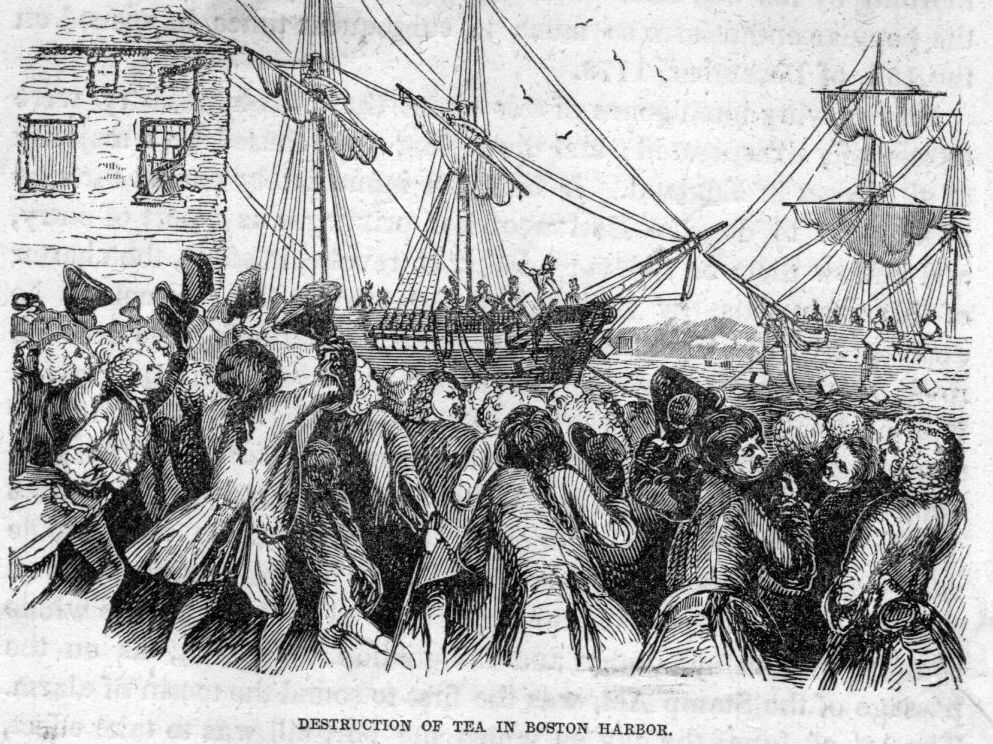

One night, a group of patriots disguised as Native Americans boarded British ships moored in Boston Harbor and chucked crates of the king’s tea into the water in an act of protest. The bold defiance sent a signal to King George III, letting him know Americans weren’t going to take any more shit from the crown and sparked the first flames of the American Revolution.

There’s just one problem — well, a few problems. Essentially, that entire narrative is false. While the Boston Tea Party was a real thing that happened on Tuesday, Dec. 14, 1773, the actual machinations of the now historical event unfolded much differently, under different circumstances, and for different reasons.

Let’s take a look at why everything you think you know about the Boston Tea Party is probably a bit off.

The Boston Tea Party Was Not a Response to a New Tea Tax

Americans hate paying taxes; this was also the case in colonial times, so it would make sense that the overt display of disobedience like the Boston Tea Party would have been spurred by yet another financial burden imposed on the average citizen from across the Atlantic — but it wasn’t. The Boston Tea Party took place due to a lack of a tax.

The British East India Company (EIC) had long supplied much of the British world with tea. But, when the world economy shifted, the company found itself with a surplus of tea that it couldn’t sell without taking a loss. King George III and his Parlament intervened and hooked the company up with a pretty sweet bailout.

The solution was to give EIC a free pass on taxes due to the crown for any tea that came into England and was then bound for the American colonies. The only fee the company would pay was a small import duty once the tea reached the colonies. This allowed the East India Company to reduce the consumer price for its tea in America while still maintaining a healthy profit that was almost entirely tax-free. Lower tea prices for colonists should have been a good thing, right? It wasn’t that simple.

The tax forgiveness for the EIC enraged the American colonists for a couple of reasons. First, it was yet another example of government decision-making taking place thousands of miles away and with no input from those it impacted.

More importantly, the new reduced-price East India tea was cheaper than what smugglers had been charging for tea they were bringing into the country from Holland. This system was working well and circumventing British taxation. The tax change dealt a direct blow to the local underground tea economy in the colonies and took money out of many people’s pockets.

It Wasn’t the King’s Tea

As mentioned above, the tea that was thrown into the harbor didn’t belong to the crown or England but to a private British entity, the East India Company.

Dumping it into Boston Harbor was more of a direct middle finger to the EIC, which was benefitting from stealing their black market tea trade, and a sort of secondary insult to King George, who actually made the taxation change. The Boston Tea Party was a rather extreme act of protest, and it certainly got the king’s attention and drew his wrath, even if it wasn’t technically England’s tea.

The Ships Weren’t British

Okay, so maybe the tea didn’t belong to the king, and neither the government nor the EIC was going to feel any pressure from the loss of the physical goods that were destroyed, but the actual ships that were raided and vandalized were British vessels, yeah?

Surely their British owners would be miffed that the colonists had boarded their ships and destroyed cargo that they had been contracted to deliver. Perhaps they would have been — if the ships’ owners were British.

Three ships were raided in Boston Harbor on Dec. 16: the Beaver, the Dartmouth, and the Eleanor. All were built in America and were privately owned, at least in part, by American colonists.

The Native American Disguises Were a Statement, Not an Attempt to Shift Blame

Usually, when someone puts on a disguise, it’s because they’re trying to conceal their real identity. Depending on the disguise, the wearer may also be trying to scapegoat a particular person or group for their nefarious actions. Therefore, it’s logical to assume the ship boarders dressed up as Native Americans to make it look like local natives had done the tea dumping — but that’s not how it went down. Even in the traditional narrative, it doesn’t make much sense.

According to Benjamin Carp, a history professor and published author on the Boston Tea Party, the disguises weren’t worn in an attempt to pin the blame on Native Americans. Instead, they were piggybacking on the image of the Native American as the ultimate anti-colonialist as part of their statement of protest against British rule, possessing an attitude of defiance, unwavering spirit, and a determination to prevail.

The people who tossed the tea wanted the king and the EIC to know it was colonists who did the deed. If concealing their identity was the only goal, they could have simply donned masks. Instead, what the participants were wearing served as more of a costume than a disguise to send a bigger message regarding the spirit of the act.

Eyewitnesses also noted that no one was really fooled by how the 100 or so participants were dressed. Still, the getups worked well enough to keep all but one man, Francis Akeley, from being personally identified, arrested, and imprisoned.

The Boston Tea Party Didn’t Directly Lead to Further Revolutionary Actions

There’s no doubt that many American colonists were less than thrilled with King George III. Still, the tossing of the tea into the harbor wasn’t the actual spark that lit the revolutionary fire, but it was a necessary precursor. King George’s retaliation against the colonies for the Boston Tea Party and its message of American defiance was the spark.

While it wasn’t the king’s tea or his ships, the British government was not pleased by what unfolded in Boston, and the EIC and the British government were deeply entwined. As a result, the king needed to reassert his dominance over the colonists and remind them who was in charge. This was accomplished by the passage of the Coercive Acts of 1774, which were known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts. It’s no coincidence that the first three applied to Massachusetts exclusively.

The first act closed Boston Harbor and put a Royal Navy blockade in place to ensure that the only things going in or out of the port were for the benefit of British soldiers stationed there. The blockade was to remain in place until the colonists compensated the East India Company for the destroyed tea.

The second act placed all local governments under the direct control of appointees decreed by the crown. Those appointees had the final say on who was appointed as judges, sheriffs, and jurors: essentially, every aspect of the law. It also restricted town meetings to one per year to prevent any further spread of what was considered to be mob rule.

The third act allowed the royal governor to move trials to other countries or even to England if it was determined “that an indifferent trial cannot be had within the said province.” This effectively eliminated the right to a fair trial by one’s peers, which flew in the face of the Magna Carta that had been in place since 1215.

The fourth and final act applied to all 13 American colonies, and it allowed high-ranking military officers the right to demand better accommodations for British troops and to refuse locations for quarters that they deemed inconvenient. It also required the colonists to provide these accommodations at their own expense. (It did not, however, require colonists to let soldiers live in their homes with them — that’s another commonly-held misconception — but in some cases, it required colonists to give up their homes to British soldiers.)

Once the colonists were subjected to the Intolerable Acts, true revolutionary sentiments began to take shape. The Acts went into place in May and June of 1774, and on September 4, 1774, the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia. From there, the rest is American history.

Relearning American History

The stories from history we’re taught as small children are almost always more complicated when you dig down into them as an adult. The events are understandably simplified so kids can absorb them and fit them into some kind of basic historical narrative, which is fine and necessary. You’re not going to explain the East India Company, British Imperialism, and how black markets and smuggling work to an 8-year-old kid — you’re just going to tell them it was the king’s tea.

But there are lots of folks who just kind of let the finer details wash over them when they’re exposed to the events again in high school or in that YouTube video they watched that one time late at night.

Also, the simpler stories are often better stories, and they tend to stick. And sometimes, the spin put on events by newspapers and pamphleteers of the time simply endures. Plus, explaining, “Actually, how it really happened was…” can sometimes feel like explaining why a joke is funny.

As we get older and wiser, we realize nothing happens in a vacuum and that there’s always way more going on than what makes it to the surface of any story. This holds true for the Boston Tea Party, but it’s also true of other events surrounding the American Revolution, such as the Boston Massacre, Paul Revere’s midnight ride, and even precisely how and when the signers of the Declaration of Independence put their names to parchment.

Read Next: Oliver Winchester and Sam Colt – Innovators and Lousy Gunmakers

Ken Perry says

I think this is mostly right but if you dig a little more you also know that the EIC was british backed which pretty much makes this attack fully on the King. All the way back from the 1600 the EIC had the backing of the crown.

In 1600, ‘The Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies’ was given ‘royal approval’ by a charter from Queen Elizabeth I. 218 subscribers raised £68,373 – a huge amount of money at a time when a skilled carpenter was earning about 7 pence a day. The Company was granted a monopoly on all English trade east of the Cape of Good Hope.