Nineteen days after leaving the White House and his second term as president, Theodore Roosevelt kissed his wife goodbye. He boarded a train in Oyster Bay with his son Kermit, bound for a steamship, bound for Africa. Roosevelt was embarking on a 15-month safari, sponsored by the Smithsonian, meticulously planned more than a year in advance, with a goal of taking enough specimens to start an American Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. In the planning, Roosevelt turned to his friend and the most famous white hunter of their day, the Englishman Frederick Courteney Selous.

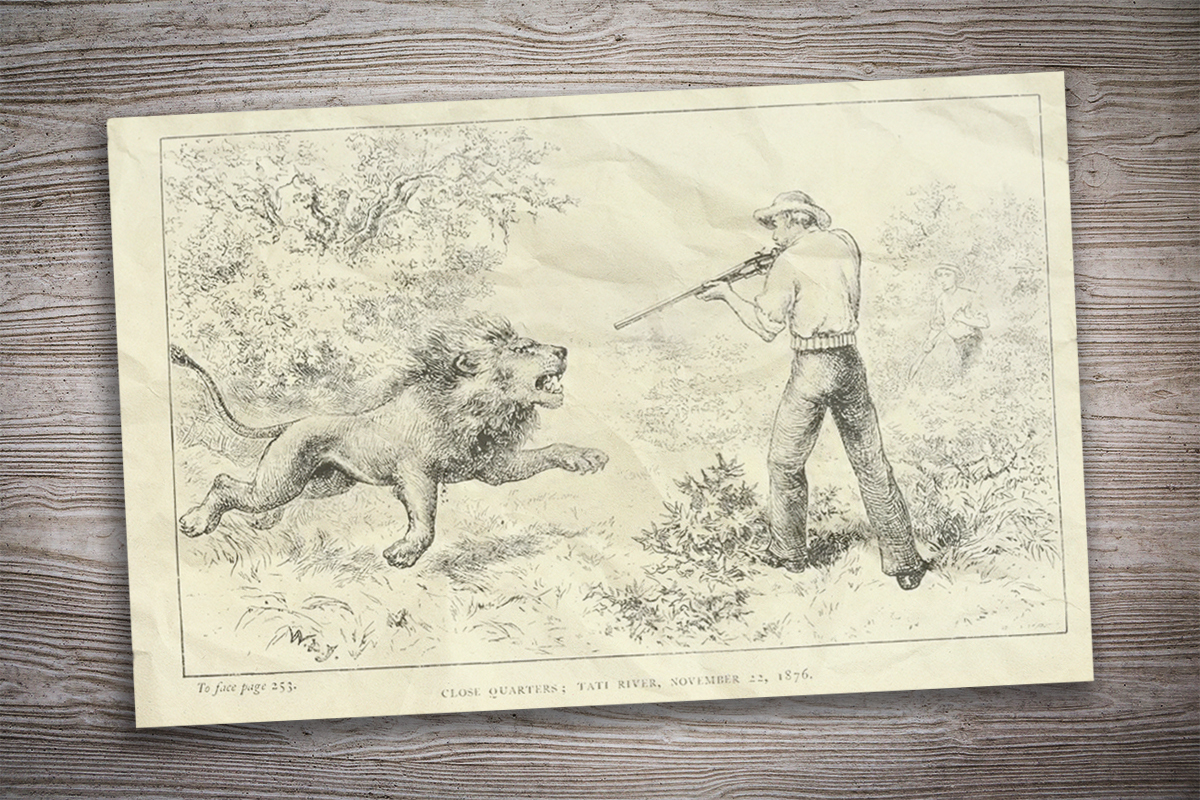

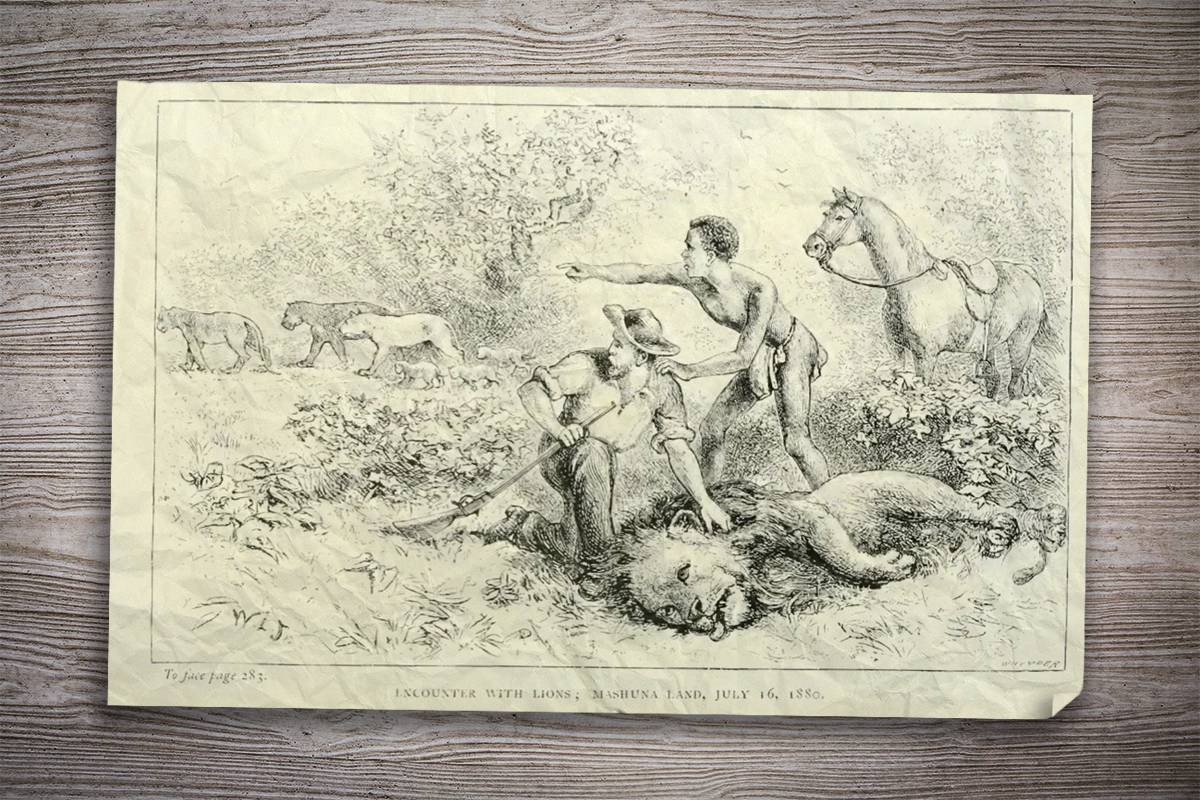

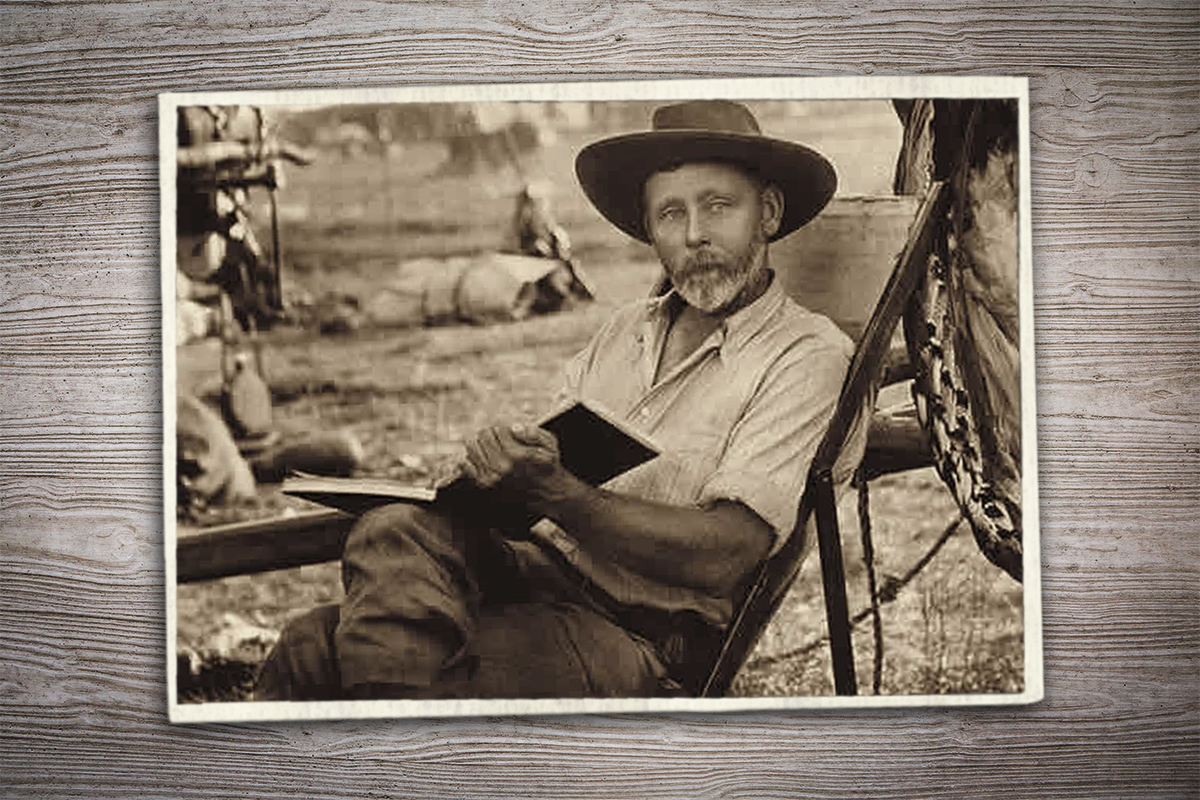

Though TR would never hunt with Selous, the two men exchanged letters for nearly twenty years. TR praised Selous’ fieldwork — with rifle, and on the page with a pen. Roosevelt fawned over A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa, Selous’ account of nine years as a professional elephant hunter in southern Africa. In the foreword to one of Selous’ later books, Roosevelt wrote that Selous’ observations on lions “represent without any exception the best study we have of the great, tawny, maned cat.” Indeed, Selous had had much experience with those tawny cats. He had shot more than thirty of them. Many of his trophies were displayed in British museums. Roosevelt saw in Selous what he tried to cultivate in himself: a hunter as expert on the lifecycles of butterflies as with a stout 4 bore.

Selous was unlike many Africa specialists of his day. He came from what a friend called “the cultured and well-to-do classes.” His father Frederick rose from clerk to chairman of the London Stock Exchange. Young Frederick “was widely regarded as the best amateur player of the clarinet in London,” according to one biographer. As a boy his parents worried about what they called his “determined single-mindedness and self-sufficiency” — traits, no doubt, that would serve him well in the bush.

Indoors, Selous lived on the books of Dr. David Livingston and the African diaries of the hunter Charles Baldwin. Outdoors, he’d disappear to the nearest field or river with a butterfly net or fishing pole in hand. He was constantly in trouble at primary school in Tottenham: sneaking out of windows in the night, returning soaking wet or without his shoes. Neighboring landowners often complained of his trespassing. Teachers were regularly shocked by the collections of bird eggs and rodent pelts that hung in his locker. In one letter home to his parents, he appealed at length for two new slingshots. His friends marveled at his acuity in the woods, spotting birds on the horizon others couldn’t see, identifying them, and what they carried in their beaks. He excelled at sports; first boxing and then rugby. His grades were poor. His taste for blood sports would soon define him.

For many boys growing up in the late 19th century, Africa was a land of danger and adventure. The books of Livingston and other explorers popularized a view of Africa as the land of noble animals and brutal savages. Raised on these stories, both Selous and Roosevelt spent their boyhoods in fields or forests, acting out their heroes’ encounters with all those strange and magical beasts. A famously sickly child, Roosevelt did not have the sheer number of youthful adventures as Selous, but as a young man he would more than make up for it in the American West, and during the Spanish-American War. Yet wherever either young man traveled, Africa was always with them as the ideal, great game-rich land or in the saddle-packed pages of their favorite books.

As a boy, Roosevelt was enthralled with Livingston. Livingston’s account in Missionary Travels of a churchman dragged off by lions stayed with TR forever. Like Selous, young Roosevelt collected every artifact of the natural world he could find. The skull of an Atlantic seal purchased at a fruit store on Broadway was an early entry in the Roosevelt Museum of Natural History, which started in his Manhattan bedroom. He kept four pet mice, wrote essays on ants and fireflies, and soon had more than 1,000 specimens in his bedroom collection.

The year Selous first left for Africa at the age of 21, Roosevelt was 13 years old and began taking lessons in taxidermy. On a family trip to Egypt, Roosevelt shot his first bird, a warbler, outside Cairo with his first gun, a 12-gauge pin-fire Lefaucheux shotgun made in Paris. He mounted a crocodile bird and lapwing he had taken on the Nile. Young Roosevelt could not stop shooting, knocking “a red-tailed chat off a column of the Ramses temple at Thebes,” according to the writer Bartle Bull. On the cruise up the Nile, the boy hovered over recent kills with a taxidermist’s scalpel and arsenic, skipping off ship at every stop, with that same single-mindedness that troubled Selous’ parents.

Skipping school worried Selous’ parents. They hoped academia in a cultivated country would temper his enthusiasm for the outdoors. He was sent to Switzerland to study medicine—an attempt to turn his penchant for animal anatomy into a respectable career. Yet Selous was soon apprehended in Germany for poaching honey-buzzard eggs. He transferred to another school in Austria but spent more time in the mountains than in the books. Later in life, he remembered the time he netted the elusive purple emperor butterflies in the hills above Salzburg, and the first stag he shot on a snowy mountain pass in the Alps. The doctor’s life was not for him, he insisted to his parents on his return to England in 1871. His father agreed and advanced him £400 and passage to Africa.

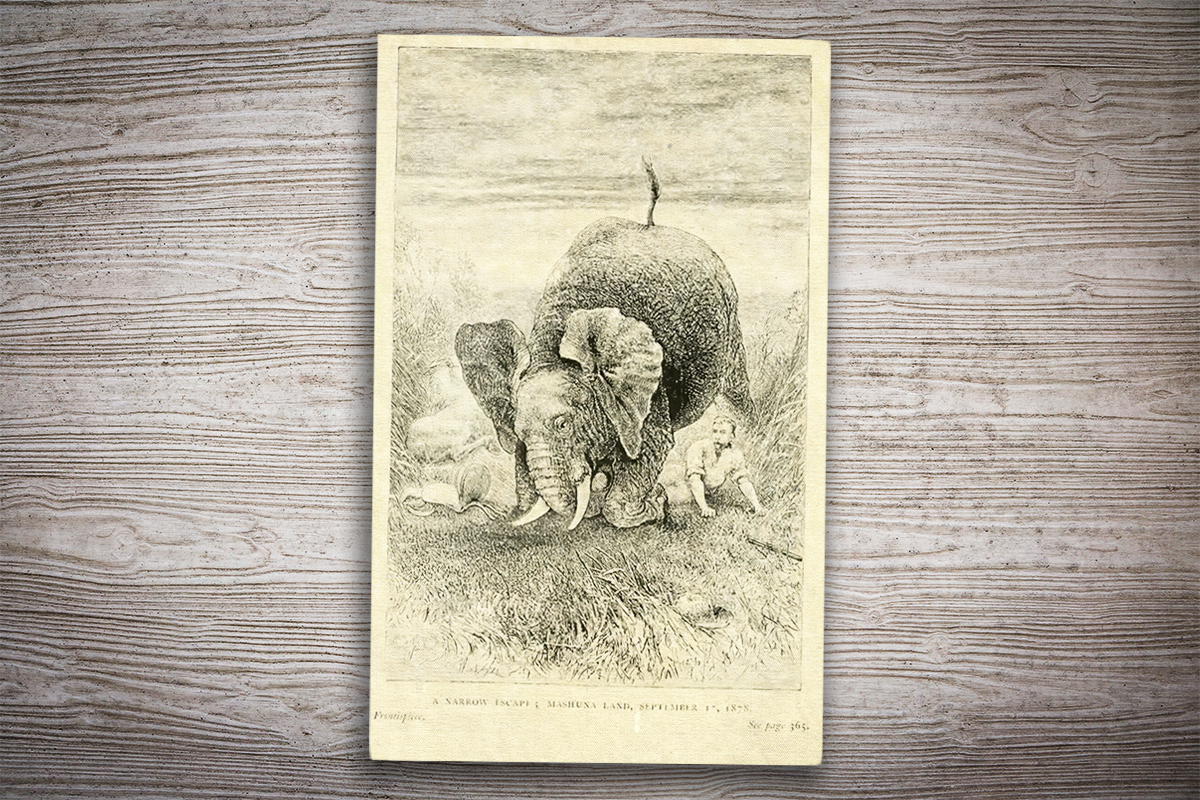

Selous set off to be a professional hunter. He hoped to make a return on his father’s money even though the heyday of elephant hunting had passed. Elephants in southern Africa had been targeted with brutal intensity since the 1850s. Ivory billiard balls graced all proper upper-class European game rooms. Ivory made the handles of the finest hairbrushes. Ivory was essential to all the world’s pianos. The elephants that were said to have roamed the open plains of southern Africa by the thousands soon met small armies of men with guns. They were a moving sea of ivory production with their numbers often compared to the bison of the old American West. Yet when Selous landed in Africa on Sept. 4, 1871, at Algoa Bay, a small inlet on the east coast of present-day South Africa, the elephants were all but extinct from the Transvaal.

Teams of Boer and English hunters on horseback had wiped out the great herds. Native hunters played their part too, often outfitted by Arab traders from Zanzibar. (One hunting party included 400 Africans armed with muzzleloaders.) The surviving elephants moved north, literally pushed by the blast of gunfire, into present-day Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique, where they joined local elephant populations. In this higher country, the giant elephant was saved by the tiny tsetse fly. The fly stopped hunters on horseback like a high wall. The tsetse fly bite could kill a horse in a matter of days. It was deadly to cattle and oxen too and made many a man ghastly ill. By the time Selous arrived in Africa, anyone interested in hunting elephants had to contend with the fly. And they had to do it on foot.

Frederick Selous, 21, traveled light with just a blanket, a bag of cornmeal, two crude muzzleloaders and two leather sacks — one for powder, the other for shot. His fine Reilly double rifle was stolen almost as soon as he arrived in Africa. For £12 he bought two smooth-bores. Manufactured by Isaac Hollis of Birmingham, each weighed 12.5 pounds. They fired four-ounce lead balls — a quarter-pound sphere a little smaller than a walnut. The recoil packed enough wallop to knock the young hunter right off his feet, which happened more than once. He spent £300 on a wagon, oxen, five horses and a keg of cheap powder. In short order, his father’s advance was spent.

Selous hoped to hunt elephants with the septuagenarian Afrikaner Jan Viljoen. He made a 400-mile trip north from the coast and crossed the Limpopo River into present-day Zimbabwe. It was the edge of fly country. Grass plains rolled out before him, spotted by solitary acacia trees, just as they had looked in the etchings of his favorite books. On the trek north, he suffered his first of many safari injuries when a companion’s pipe ignited a box of loose powder. He spent a week convalescing, his burned face, neck, and arms covered in a mixture of petroleum jelly and salt. Selous marveled at his first wild herd of giraffe and failed to kill one. He later passed on a shot at an old bull giraffe since the meat was known to be “rank beyond consumption.” He spent two nights alone in the bush after losing his companions from chasing that first herd of giraffe. He had lost his horse and nearly died from dehydration. When he finally met up with the legendary hunter Viljoen, Selous cut his foot at the Boer’s campsite; it sprouted an infection, and the hunting party moved on without him.

Convalescing, living off local corn, and whatever antelopes he could shoot near camp, Selous befriended a Khoi hunter nicknamed Cigar — named so by white hunters who had seen him hunting in native fashion, without pants. Selous would later call Cigar “the best shot in Africa.” Together they struck out for elephants. Cigar had worked for the famed English hunter William Finnaughty. Now Selous was Cigar’s apprentice. They set up a base camp on the edge of tsetse country with wagons, supplies and Matabele porters, gun bearers, and guides. They set off on foot into the high brown grass and rolling mopane forests of southeast Africa.

That first night Selous and Cigar shot a bull eland and grilled its steaks on an open fire. The next morning, while moving through the scattered trees and long grass, they spotted spoor — elephant tracks like sinkholes of matted grass and weeds. When Selous finally saw his first elephant, he wrote in his first book A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa, “my heart beat hard with joy at the near prospect of at last beholding an African bull elephant, and perhaps managing to shoot him.” The elephant uprooted grass, dirt to mouth. Selous and Cigar dropped their gear and took off their pants. Selous would call it “nice light running order” — long cotton shirt, felt hat, shoes, and a good breeze.

The bull elephant had ears as big as bedsheets and fanned them lazily in the sun. Its trunk occasionally checked the wind, swinging slowly in the air. Elephants make up for poor eyesight with excellent hearing and sense of smell. “We advanced quietly upon our victim, who stood broadside to us … until we were within sixty yards,” Selous wrote in A Hunter’s Wanderings. The bull wheeled around, ears spread, head high. It spotted them and both men froze. The bull took a few steps toward them, stamped the ground. “Fire,” Cigar whispered to Selous. “Fire.” Selous leveled the irons at the elephant’s shoulder. Squeezed … The noise of the gun surprised him, almost knocked him over, and the elephant staggered backward. The bull broke into a run. Cigar put another four-ounce shot into its side. The elephant wavered with the second shot, dizzy as if it were drunk. Selous and Cigar charged in. The elephant staggered as it ran off. Selous reloaded, worried that he’d lose the bull if he took his eyes off him for even a second. After a good foot race, the two hunters caught the tusker. Twenty yards away Selous steadied his gun and fired. He struck the bull again in the shoulder. The animal fell to its front knees. Selous and Cigar raced toward it, reloading. The elephant tried to get up. “One more bullet in the back of the head from Cigar’s rifle snapped the cord by which he hung to life,” Selous wrote. “He was a grand old bull.”

That was the first of dozens of elephants Selous would kill as a professional ivory hunter in Africa. Its tusks weighed 61 pounds and 58 pounds, respectively. At the time, a single 50-pound tusk was worth about £20. By the end of that first season hunting, Selous had taken 450 pounds of ivory and traded with the Matabele for nearly 1,200 pounds more. After paying off a few small debts, he profited £300 that first year in Africa—roughly $32,000 in today’s dollars.

The popular Victorian imagination swooned over the bloody accounts of hunting in Africa. There were the feasts with local kings, war dances by hundreds of assegai and ox shield-clad warriors, topless women, and tales of starry nights on beds of cut grass. The safari industry had not yet taken hold in the late 1800s. Roosevelt, despite all his travels, wealth, and daring spirit, had no ready access to the magic of Africa, save through the words of men like Selous. Then a young assistant secretary of the Department of Navy, Roosevelt was enthralled. Shortly after reading A Hunter’s Wanderings, Roosevelt wrote to Selous, “You have the most extraordinary power of seeing things with minute accuracy of detail, and then the equally necessary power to describe vividly and accurately what you have seen….” It was the first of many letters the two men would exchange.

Roosevelt had a professional interest in writing about nature. Two years before penning that first letter to Selous in 1887, he published his second book, Hunting Trips of Ranchmen, about his two years running cattle in the South Dakota badlands. Roosevelt wanted to see Selous tackle the American West the way he had Africa. In those early letters, Roosevelt offered at several points to help Selous plan a long-anticipated North American hunting trip. He offered advice and contacts but Selous made arrangements through another American friend. Selous hunted from a ranch near Yellowstone, but after expressing financial concerns — concerns that would trouble him his whole life — he returned to England via Canada and had to pass on a visit with TR in New York. A year later Selous returned to the United States to hunt mule deer in Wyoming’s Big Horn Mountains and again missed meeting TR face-to-face. Back in England, he wrote Roosevelt that he was disappointed with the size of Wyoming’s muleys.

The letter bothered Roosevelt, who replied, “Your letter made me quite melancholy — first to think I wasn’t to see you after all; and, next, to realize so vividly how almost the last real hunting grounds in America have gone. Thirteen years ago, I had splendid sport on the Big Horn Mountains. I was just in time to see the last of the great wilderness life and real wilderness hunting …”

The idea that time was running out for a sportsman wanting to experience “great wilderness life” was particularly powerful for Roosevelt. This was especially his feeling about Africa. Roosevelt wanted to see the open plains and wild animals that captivated his boyhood nights. He wanted to hunt it. These desires played directly into his developing conservation ethic.

Selous, for his part, was an early and outspoken advocate of bag limits. Roosevelt enthusiastically supported these ideas, but unlike Selous, Roosevelt’s professional accomplishments allowed him to do something about it. With each professional development and political victory, TR found himself in a better and better position to actualize his conservation philosophy. That assistant secretary of the Navy, who first wrote Selous, was shortly thereafter elected the Governor of New York, and two years later rode into the White House as vice president on the McKinley ticket. When McKinley was shot and killed in Buffalo, New York, in 1901, TR became at 42 years old the youngest person to ever hold the office of President of the United States. Eight months into his first term he established five National Parks. He went on to add 150 National Forests, 51 federal bird reservations, four national game reserves, 18 National Monuments, and 24 reclamation projects. According to the National Geographic Society, he is responsible for placing 230 million acres under public protection.

For Selous, despite Roosevelt’s accomplishments and their similar vision, the friendship was an odd one. After his professional hunting days, Selous prided himself on only taking animals for meat or because they presented an exceptional trophy. (Game for the table or the museum only.) Roosevelt was a little different. He loved to shoot much like he was still thirteen years old. He wrote to a friend during his ranching days that he must shoot an American buffalo “before they’re all gone.” He often took long, wild shots — his shooting famously bad. This would be compounded in Africa thanks to his loss of vision in one eye due to an impromptu boxing match in 1904 at the White House.

By one account, TR enthusiastically told Selous of a cougar hunt in the West that ended when a pack of dogs tore the cat apart. Selous, according to his biographers, was quietly horrified. But Roosevelt’s sheer knowledge of the natural world, his ability to rattle off the details of native plants from continents he’d never before visited, was nothing short of astounding — and impressed the naturalist in Selous to no end. In sheer information on animal habits and behaviors, he was Selous’ intellectual superior. Indeed, Theodore Roosevelt was most men’s intellectual superior. And he was also President of the United States.

Selous never lost sight of his friend’s political power. During the Second Boer War, he wrote TR letters requesting political intervention: “I believe in my inmost soul that it is not a just war, that it could have been avoided, that it can bring this country [England] no honour, and that it will be the cause of much future trouble.” Roosevelt wrote back, “How I wish you could be made Administrator of all of South Africa. Somehow I feel you could do what no other man could, and really bring about peace.”

The Smithsonian safari to Africa was the first trip the president took after leaving office. He sorted most of the details from his White House desk. In his letters to Selous about the Africa safari, Roosevelt’s anxiety about not being seen as a naturalist are everywhere, so tuned was his thinking to political ramifications. “As you know I don’t have the slightest desire to be a game butcher,” he wrote in April 1908. Then a few months later: “In fact I particularly want to avoid anything that will savor of butchery.” It was a constant refrain. In the same letter, he worried about whether he’d bag a lion, writing to Selous, “I do not have much expectation that I will get a lion, for to judge from your experience it will be a matter of chance if I run across one at any time during my trip.”

Though the British colonial government would charge license and permit fees for every animal TR and his son shot, lions were still considered a dangerous pest across Africa. They could be killed on sight, in any number. When Selous told Roosevelt in December 1908 that he would be in Africa at the same time and that their paths may cross, TR wrote back, “Three cheers! I am simply overjoyed that you are going out. It is just the last touch to make everything perfect. But you must leave one lion somewhere! … I do not really expect to get one anyhow.” Selous had told Roosevelt that he planned to target lions too. He not only wanted a big cat, but one with a deep black mane — a true trophy, he thought.

The two white hunters recommended by Selous oversaw the caravan, which included three scientists and a taxidermist from the Smithsonian along with more than 250 native porters and guides. Roosevelt brought with him a small library of books bound in pigskin. Worried about the president’s comfort, Selous drew up a grocery list of pate de foie gras, tinned prawns, and French plums. TR crossed them off for baked beans, tinned tomatoes, and tinned peaches. Selous proposed a gross case of whisky to which Roosevelt responded, “I never take whisky on a hunting trip except for sickness.”

For his part, TR fretted over guns. Henry Sharp recommended the president carry a ball and shot gun, an idea which TR suggested to Selous. The old elephant hunter wrote back at length: “No doubt such weapon might be very useful in certain parts of the world, but I think it would be less useful in Africa than in almost any other country … I know that anyone who has shot much in Africa will agree with me that with your small bore Springfield rifle for the game of the open plains, your Winchester .45-70 for open bush country where you could get nearer to game than on the open plains and your .450 bore cordite rifle for heavy game, you will have all the weapons you really require … If you have an old scatter gun it would be as well to take it along with you to shoot guinea fowl and ducks for the pot.”

Selous was excited about his own return to Africa and was grateful to his American publisher, who would host him at his ranch. TR would be nearby, at the ranch of Sir Alfred Pease, but the safaris would move in separate directions. Selous wouldn’t have it any other way. He confided in a friend: “His party is so large, and I don’t want to be with a crowd.”

There is a photograph of Roosevelt and Selous taken aboard the steamship Admiral en route to Mombasa. The two men spent much time in deck chairs trading stories, surrounded by admirers — passengers amazed at their luck, traveling with a former president and one of the most famous Englishmen the world over. TR is laughing in the photograph; his white teeth blazing beneath his thick brush of mustache, wrinkled nose and small bespectacled eyes squinting. It is a laugh that looks like a roar. Selous is leaning forward, smiling. Perhaps he just delivered the punch line of a well-honed Africa tale. The 57-year-old Selous seems wiry beside the President. Selous was always lithe and remarkably agile, built for running. And by all accounts, he was a hell of a storyteller.

Just before departure, when Selous announced he wouldn’t be hunting with TR, the collective press seemed to gasp, worried about the president’s safety. Selous tempered concerns by endorsing the white hunters that planned to accompany TR, and added, in one interview, that he was “coaching” the President in the fine art of lion killing.

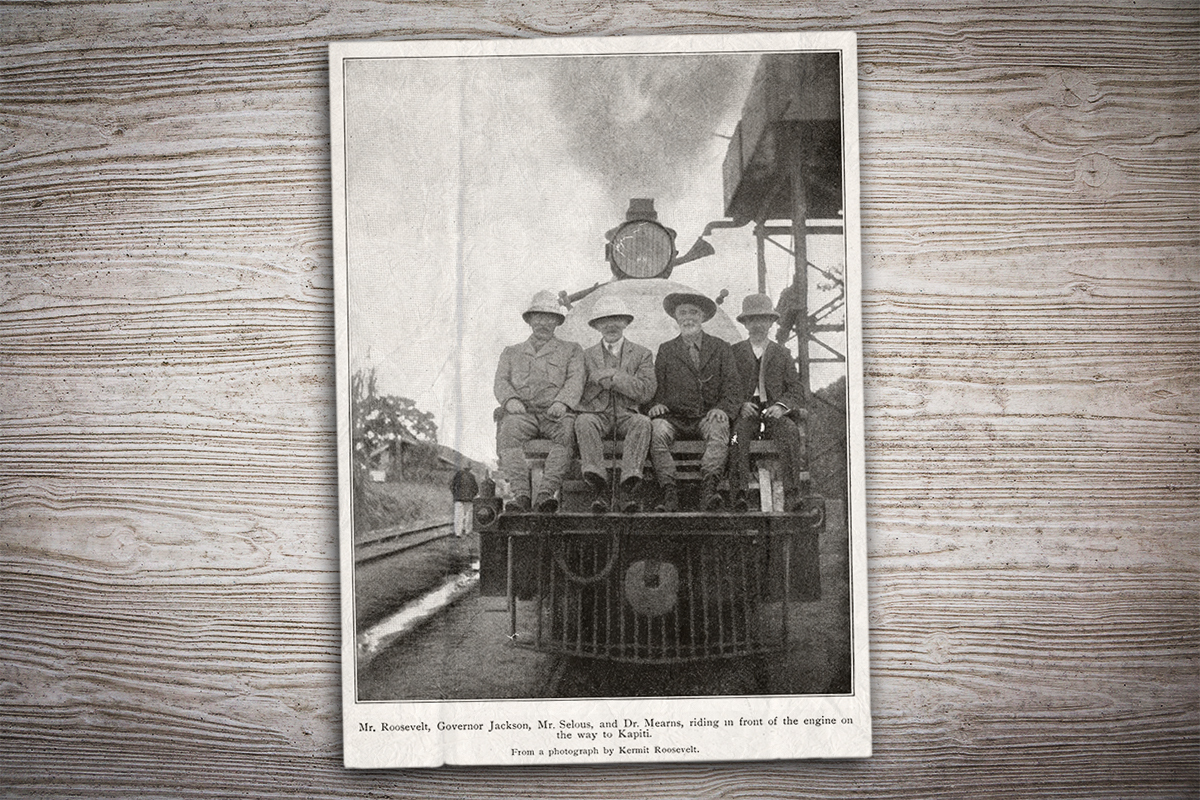

After the Admiral docked in Mombasa, Selous and Roosevelt rode the Uganda railroad toward Nairobi, on a bench affixed to the cowcatcher. The train’s metal beak was bent and twisted from a late-night collision with a rhinoceros. Roosevelt marveled at the landscape — a rolling ocean of golden grass. He was awed as Selous had been awed when he saw his first herd of giraffe on the open plains. For TR it was happily “the Pleistocene” — that untouched wildness where he could run down the hunted. From that open-air bench, TR clearly couldn’t see the tons of men and gear the train carried behind him.

From the Pease ranch, Roosevelt charged forward, onto one of the largest African safaris ever mounted. His praise of white hunters as guides helped create the modern safari industry. His accounts of the shooting in Scribner’s magazine and then in the book African Game Trails would supply that industry with hundreds of paying, thrill-seeking Americans from Hemingway to Gary Cooper.

Selous would return to Africa. At the outbreak of World War I, at 65 years old, he petitioned the War Office for frontline service. The response was quick: “age prohibitive against employment.” But soon after he was turned down, the East African campaign fell to shambles for the British. At Tanga, the Germans outfought inexperienced Indian troops with one-eighth the men. The War Office mobilized all the Africa hands they could muster. Selous was made a captain. His men said he could out-march any one of them.

Selous and his men took heavy German fire on a ridgeline over the village of Beho Beho in British East Africa. Selous slid down the ridge, 15 yards forward. He could not see the Germans, lying protected among the scattered trees and high brown grass. In the clearing, he just lifted his binoculars when the first bullet clipped his side. Selous wheeled around, wavered. The German sniper shucked his bolt and sighted him again. Selous looked back toward his men. The second bullet ripped through the side of his head.

Selous was buried not far from where he died, outside the village of Beho Beho, with six other Fusiliers killed in action. His body was sewn into a simple cloth blanket and lowered down beneath the open grass he first admired on those early elephant hunts in South Africa. Appropriately, elephants roamed the open bush where the grave was dug. At the end of the war, those beside him were exhumed and reburied in proper British cemeteries. Selous was left in the bushland. The country is now Tanzania, and Beho Beho is a safari camp inside the Selous Game Reserve. His grave is marked with a simple bronze plaque. On the news of Selous’ death, Roosevelt wrote, “I greatly valued his friendship. I mourn this loss; and yet I feel that in death, as in life, he was to be envied.”

This article was originally published Oct. 20, 2011, on Outdoor Life.

Read Next: How North Dakota’s Badlands Made Theodore Roosevelt One of America’s Best Presidents

Comments