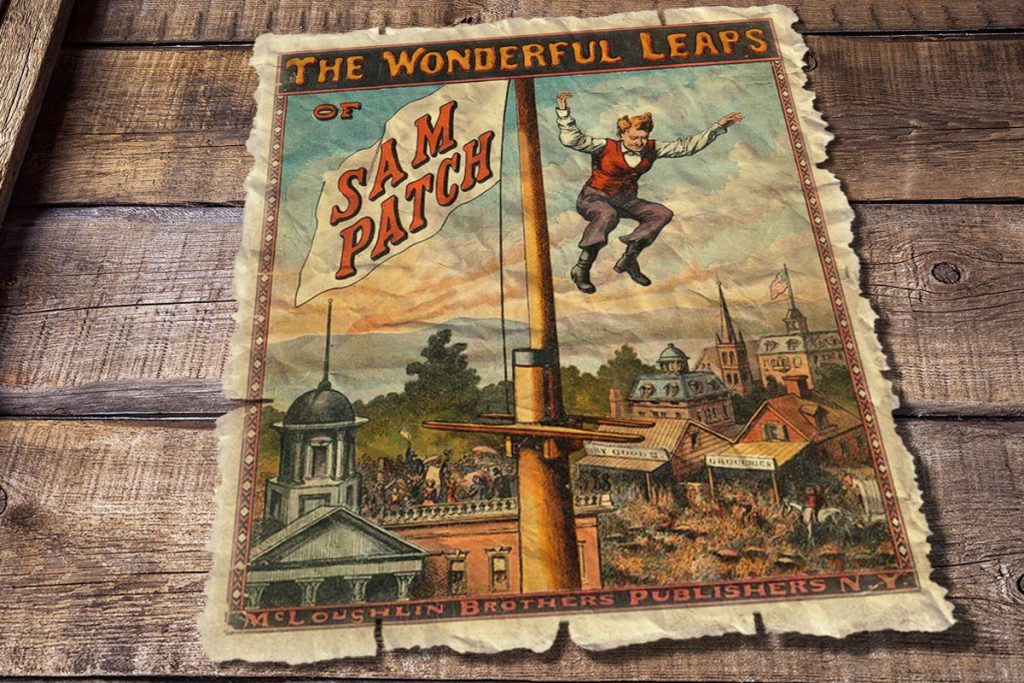

Long before Evel Knievel, Travis Pastrana, or Smagical, Sam Patch was launching off Niagara Falls for money, wowing crowds, and, notably, not dying in the process. America’s first daredevil was the original extreme sports badass — and here are six reasons you should remember his name.

He got his start as a child jumping off bridges.

The Massachusetts farm boy who was born around 1807 had a monotonous job in a cotton mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. But that’s not what excited him to wake up every day. For a brief break each afternoon, Patch and other hooligan teens from the cotton mill raced to the top of the Pawtucket Falls bridge in order to hurl themselves off it. He noticed early on that he was different from the pack because when all the other kids hesitated, he was airborne.

He was a hardworking blue-collar guy with big aspirations.

Jumping off bridges didn’t pay the bills at first, but that was only because he had nobody to entertain. He moved to New Jersey to work for himself doing the same job as a cotton spinner. When that failed in 1827, he had an epiphany. He passed a crowd watching Timothy Crane — an entrepreneur who had purchased the mill workers’ picnic grounds and converted them to please the upper class — move a large wooden pre-constructed bridge over the Passaic Falls. It was a big event, and all the workers had the day off. Wearing only a shirt and his underwear, Patch moved past an officer, and once he’d gained the attention of the spectators, he prepared for the 80-foot leap into the abyss.

“He took a couple of small stones in his hand and went to the brink of the cliff and dropped them off one after the other, and watched where they struck the water down below,” William Brown, a witness of the spectacle, recalled. “Then he walked back a few yards and turned and took a little run to the brink of the cliff and jumped off, clearing the rocks about ten feet. He went down feet first, but with his body inclining considerably to one side, and in this shape he struck the water and disappeared. A few seconds later his head bobbed up at a point down stream, and he began paddling for the shore. The crowd gave him a big cheer.”

He escalated to really freaking high bridge jumps.

The newspapers began calling him “Patch the New Jersey Jumper,” and the one-man thrill ride took it all in at a neck-breaking pace. His fearlessness became a concern, not so much for his safety but for others who might copy him. The Rochester Daily Advertiser reasoned, “It has been a common thing for persons to leap from the large stone six-story factory, below the bridge into the whirling and boiling current eighty feet below, and we have never heard of any accident has yet happened.” They even tried to explain the science, calling the aerated stream of the falls “nearly as soft as an ocean of feathers.” Note: This is total bullshit. At 80 feet, the jumper hits the water and the water hits back.

On Aug. 11, 1828, with three jumps at the Passaic Falls to his name, he escalated to 100 feet. He gained a reputation, falling in style from a 90-foot platform while a crowd of 500 to 600 people watched from the lawn of Van Buskirk’s Hotel and from a flotilla of boats in the water nearby. His technique was to land feet-first with a minimal splash.

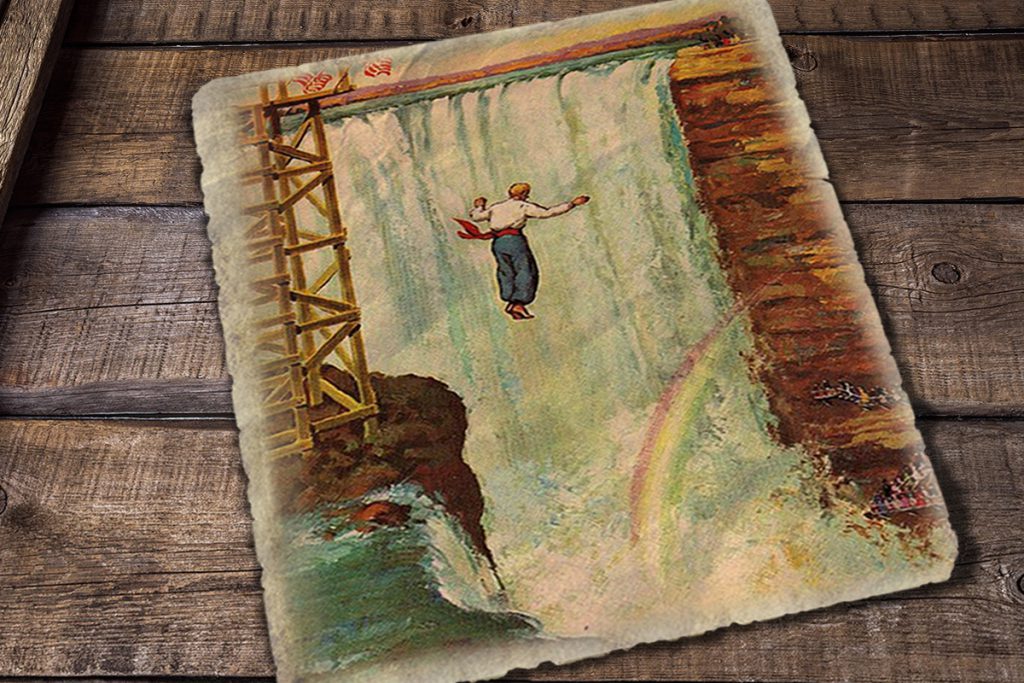

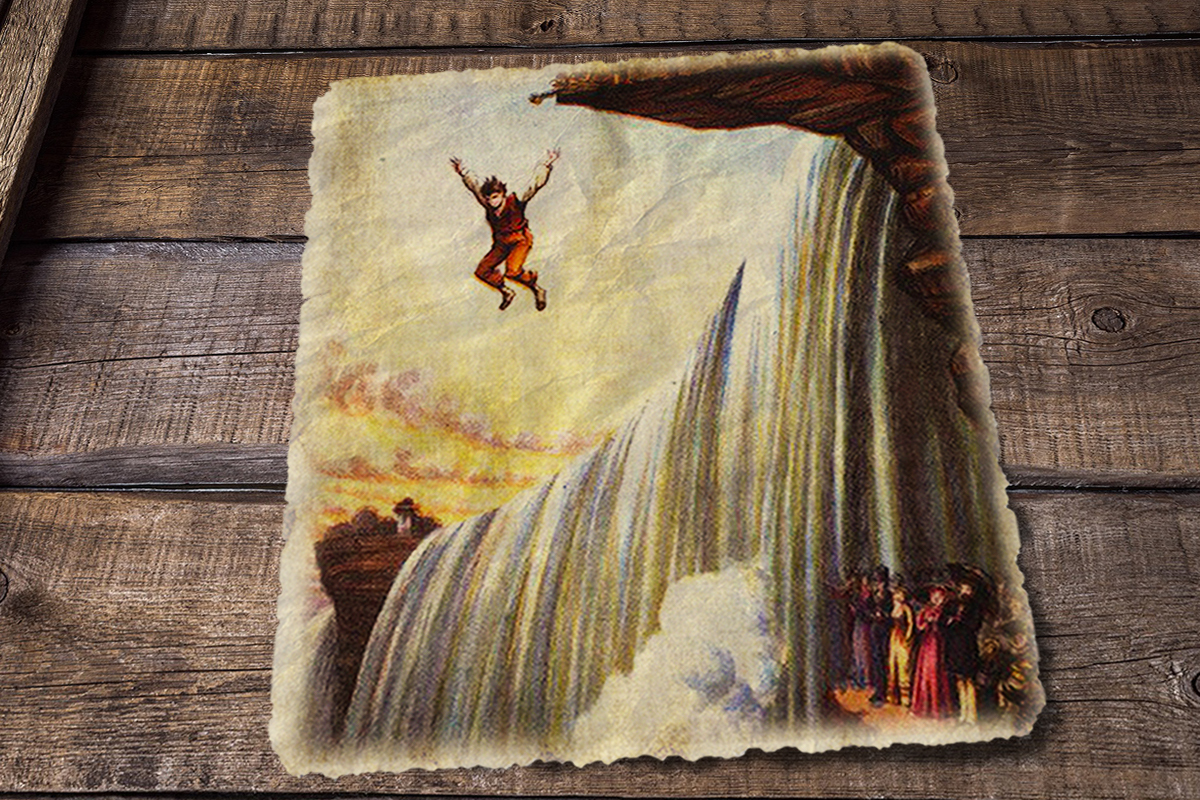

He jumped Niagara Falls — twice.

In the fall of 1829, businesses near Niagara Falls organized a series of exhibitions to attract tourists. Demolition experts used dynamite to explode sections of rock, and a schooner was pushed over the falls as spectators watched it wreck at the bottom. However, Patch the waterfall jumper was the main attraction.

“A ladder was projected from Goat Island about 40 feet down, on which Sam walked out clad in white, and with great deliberation put his hands close to his side and jumped from the platform into the midst of that vast gulf of foaming waters from which none of human kind had ever before emerged in life,” wrote New York’s Evening Post. “Sam Patch has immortalized himself — he has done what mortal never did before — has precipitated himself eighty-five feet in one leap; that leap into the mighty cavern of Niagara’s Cataract; and survives the romantic feat uninjured!”

Some among the audience thought the jump was rigged. So on his second jump, met with gasps and cheers as he emerged from the swirling rapids, he fired off what became an effective, if corny, tagline: “There’s no mistake in Sam Patch!”

He had a pet bear.

Niagara Falls was seen as the pinnacle of waterfall jumping, yet Patch argued the High Falls of the Genesee River in Rochester, New York, was of equal peril. He had acquired a pet bear while traveling through Buffalo and promised his new animal companion would leap too. On Nov. 6, 1829, Patch and the bear stood in view of 6,000 to 8,000 onlookers.

“He took the bear by the collar and pushed it over the Falls into the turbulent water below,” wrote city historian Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck for the Rochester Public Library. “The bear struggled safely to shore. Patch leaped after.” Hard to say how the bear felt about him after that.

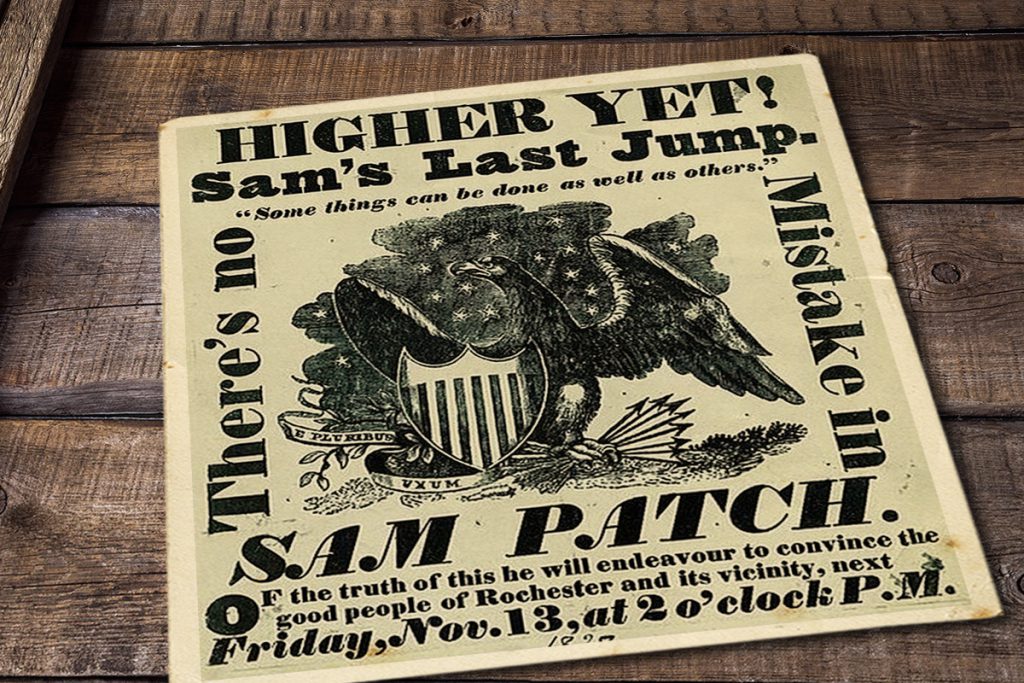

His second High Falls jump killed him.

The following Friday, Nov. 13, Patch scheduled a second jump from the same exact spot. He was disappointed in the amount of money he had earned on his first, considering there were thousands of people watching him risk his life. Advertisement posters promised, “Higher Yet! Sam’s last jump.”

From a platform 25 feet over the Genesee Falls — for a total height of a whopping 125 feet — Patch stood proudly and offered a grand speech before his dive. “Napoleon was a great man and a great general,” he said. “He conquered armies and he conquered nations, but he couldn’t jump the Genesee Falls. Wellington was a great man and a great soldier. He conquered armies and he conquered nations and he conquered Napoleon, but he couldn’t jump the Genesee Falls. That was left for me to do, and I can do it well.”

He put his arms to his sides, stepped beyond the platform, and plummeted toward the water. He disappeared below the surface and never came up for a breath. The crowd waited in silence.

Sam Patch’s body was recovered four months later, 7 miles downstream. His legacy is often forgotten in relation to modern-day daredevils, but for the era, he was a living legend. In 1833, President Andrew Jackson immortalized Sam Patch when he named a white stallion in Patch’s honor. There is no record of the horse ever jumping off a waterfall.

free embroidery designs says

They are so adorable such a great work.