It’s a dreary winter afternoon in Huron, South Dakota. Standing in his safety gear — hard hat, coveralls, harness — mechanic John Tapken is ready to get back to work on trains. It’s a few hours past lunchtime, but the day is far from over. Locomotive repair season is in full swing and a handful of recent arrivals are fresh off the snow-covered rails.

“These guys have 3,000 horsepower and weigh over 360,000 pounds,” says Tapken, walking through Huron’s 114-year-old roundhouse, a once common factory-meets-train-yard where the nation’s trains still go for repair. “When you add in the 4,000 gallons of fuel and 300 gallons of oil you are looking at half a million pounds going down the rail.”

The United States’ expansion and rise as the world’s preeminent economic superpower couldn’t have been done without railroads and the people who built them. These trailblazers embarked on an endeavor that would change the course of American history. Yet in an era of jetports, freeways, and fiber optics, the American rail system seems almost archaic — an afterthought from a bygone era.

But the trains still chug on. Railroads remain one of the most efficient forms of transporting goods across these United States. The rail industry still employs well over 100,000 workers and generates billions of dollars in profit that greatly benefit the nation’s economy. Without railroads, the United States’ economy would roll, effectively, to a halt.

Yet a major question remains. In today’s modern political climate, what is the future of the nation’s railways? Undoubtedly, railroads will always be a part of the backbone that keeps America’s economy chugging along, but many involved in economic and transportation policy envision whether or not railways will undergo significant changes in the future — primarily in terms of energy.

In the early 19th century, America’s first steam locomotive and steel rail system was developed. Over the next few decades, nearly 10,000 miles of track would be laid east of the Missouri River. But that was only the beginning. Leading up to the Civil War, American leaders had a bolder vision to further America’s prosperity to develop the country’s first transcontinental railroad that would connect the country east to west.

By 1869, this goal was accomplished after years of dangerous and arduous work completed predominantly by immigrants as well as Civil War veterans. With their efforts, trains and the railway would prove to be a catalyst that initiated unparalleled economic development and would eventually upend the nation’s canal system as the most feasible and fiscally sound way of transporting goods across the country. It also provided an efficient and affordable way for people to travel across the rapidly expanding nation.

The next major railway expansion would spark mass settlement in the Upper Great Plains and Dakota Territory. This prompted railroad pioneers to set up the task of completing thousands more lines of rail in the relatively unknown and uncharted lands.

One of those men was Marvin Hughitt, a rising star within the railroad community who had played an integral role in hauling cargo and troops for the Union along Northern railways during the Civil War. His grit, gumption, and knowledge of railroad operations would propel him to serve as superintendent and president of the Chicago and North Western Railway, as well as managing various feeder lines throughout the region.

A particular area in the James River Valley caught his eye: one that would eventually become one of the hotbeds of railroad operations in the region and still be as essential well over a century later. Welcome to Huron, South Dakota.

“The railroad’s establishment and location of Huron in 1879 was very deliberate,” said Rick Mills, museum director and curator of the South Dakota State Railroad Museum. “President Marvin Hughitt and Dakota Central Railway/Chicago and North Western officials personally chose the location at a point approximately halfway between the division point at Tracy, Minnesota, and the eventual terminal on the Missouri River — established as Pierre in 1880. The line was intended to be a main line between Chicago, southern Minnesota, and the Black Hills.”

In just a decade’s time since the first rails and passenger depot were created, Huron’s population experienced exponential growth. A bare-bones settlement went from more than 100 people to more than 3,000 residents — a drastic increase. Dozens of new businesses began to appear in the area. Main Street, which ran north and south of the railroad tracks, became a large economic hub for the prospering town.

“The railroad depot, whether the town was big or small, was the epicenter of the community. Along with transporting people, any merchandise, supplies, baggage, you name it — everything was done by the railroad,” Mike Lenzen, former president of the Chicago North Western Historical Society, said.

Huron’s rapid rise and economic prowess due to the railroad’s influence made it a contender for the state’s capital — which eventually was settled on the railway’s opposite terminal on the Missouri River in Pierre in 1904. But that didn’t hinder the small town’s aspirations of further growth and development.

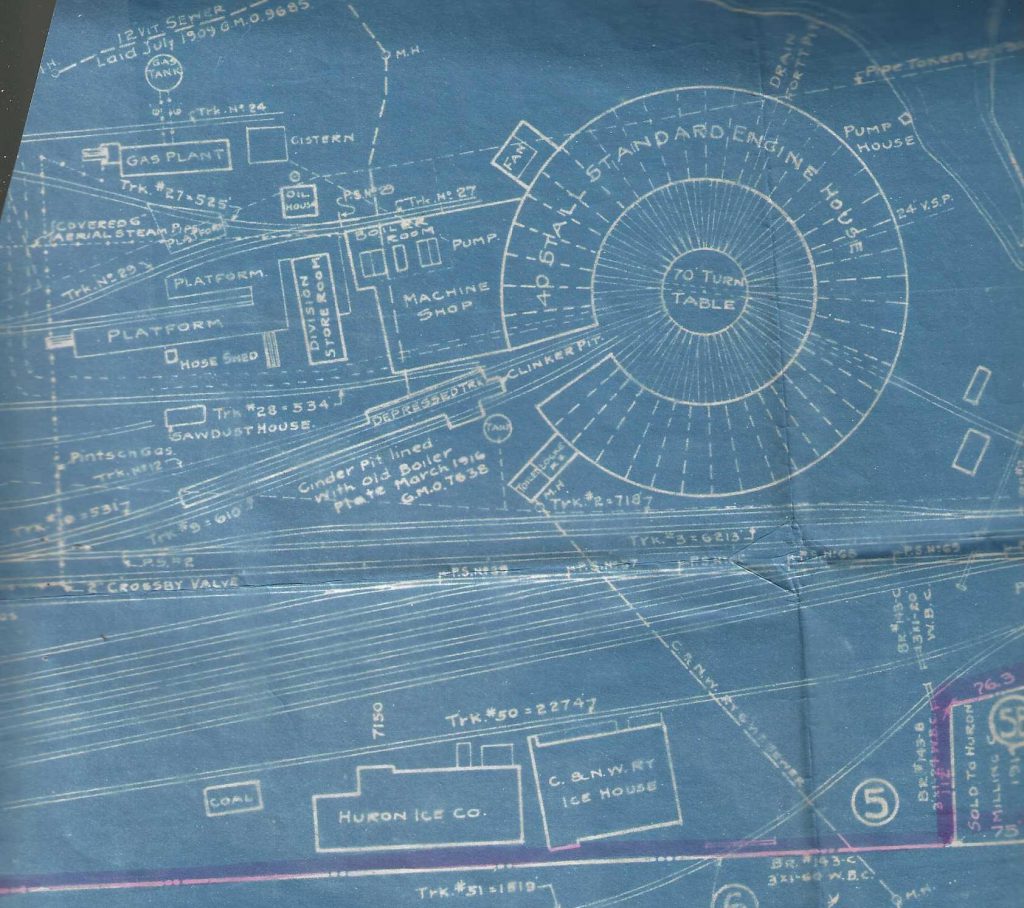

Coinciding with the constant traffic on the railway, Huron’s rail presence endured another significant boost with the decision to create a roundhouse in 1907, which was integral to any repairs, maintenance, and storage of the steam-powered trains heading westward. The circular or semicircular building had what amounted to a turntable on tracks at its center. A train would ride in, then the track disconnected, the floor and rails rotated under the train, and the track connected to a stall where the train could be off-loaded for storage or repair.

Each stall had pits where workers could get underneath the locomotives to investigate and do repairs. The ability to rotate the locomotives was essential, since most steam-based locomotives could only run forward. This allowed roundhouses to rotate them in and out of service, or turn them around back toward from where they came. The establishment of Huron’s Roundhouse in 1907 sparked further prosperity for the town. In the next decade, the railway would become the town’s major employer and by 1920, Huron’s population doubled again, making it one of the largest towns in South Dakota.

Huron’s roundhouse was built to stand the test of time with brick floors and brick siding. It had 40 stalls that were 82 feet long and a 70-foot electric turntable. Additionally, it featured two drop pits, which allowed for major repairs that couldn’t be done at other roundhouses that lacked them.

“Only the largest locomotive facilities had drop pits. Picture a steam engine having troubles with a set of wheels that needed to be changed out. The railroad workers would be able to go into those drop pits underground and make repairs or replacements with the wheels or other parts as necessary. This is an indicator that it was a good sized facility,” said Lenzen.

“Huron’s rail presence was significant. The railway’s superintendent and dispatchers were located there. It was the access point for rail operations for Chicago and North Western for many years,” added Lenzen. “In addition to the Roundhouse they had all sorts of ancillary buildings. They had the passenger depot, a blacksmith’s shop and carpenter’s shop, a freight house, offices, gas plants, paint shop, icehouse, and rail mill. They had all sorts of ancillary buildings.”

Huron’s roundhouse and railways continued to roar and be an apex in the region through World War II and the middle of the 20th century. Alas, the creation of the automobile and airplanes inevitably meant they would begin to lose some of their importance. In particular, this would have a significant impact on passenger operations, with its last passenger train journey out of Huron to Chicago occurring in 1962.

By the 1970s, many of the railways that had transformed the region and country would become abandoned. Trains would ultimately become diesel-based as opposed to steam-based, which in turn meant more efficiency and less need for repairs. Huron’s roundhouse, which was once a complete circle and 40 stalls large, would eventually be reduced to 16 stalls. In the 1980s, Chicago and Northwestern would sell what remained to the Dakota, Minnesota & Eastern Railroad.

While many of the surrounding area roundhouses closed, a century later, Huron’s still stands. The endeavors of the roundhouse are still important to the region’s vitality as they were in the 20th century. Currently under the ownership of Genesee & Wyoming, the Rapid City, Pierre & Eastern Railroad has remained a crucial cog for the local area and surrounding communities’ economic viability.

The dominant tonnage that is hauled through Huron by train consists primarily of agricultural commodities such as wheat, corn, soybeans, and fertilizer. In addition to those, bulk and bagged cement, aggregates and stone products, as well as bentonite clay, all make their way through Huron’s facility.

Railroads are classified by the amount of revenue they bring in. Huron’s location serving the DM&E railroad is a Class II railroad line (the most common), defined by the Surface Transportation Board as midsize rail operations with annual revenues between $20 million and $250 million. Class I is defined as an annual revenue exceeding $250 million. Class III, or short line railroads, operate with an annual revenue under $20 million. Most of America’s rail lines are Class III, with only a handful of Class I still in existence.

“Huron remains as a significant railroad terminal in South Dakota. The RCP&E roundhouse and locomotive facility is the most active still operating in the state,” said Mills. “Additional rail car maintenance, car classification, and train operations east, west, and north keep the terminal busy.”

The significance of Huron’s rail operations are well known to those who live there, but moreover, those who work there. Longtime Huron resident and native John Tapken, a locomotive mechanic for the RCP&E, has been with the company for over 12 years. While the railroad has endured several changes in ownership over the past few decades, the belief in their mission and pride of what they do on a day-to-day basis is as strong as ever.

“Deep down, us railway workers know if it wasn’t for the railroad Huron wouldn’t be here. Its historical importance is significant. But even to this day, we still service many large and local businesses,” said Tapken. “We have around 70 employees based out of Huron. All of us spend money locally and have families. We might not be the biggest company in town anymore, but we have been here the longest.”

In addition to hauling the aforementioned freight, the tradition of repairing and maintaining the trains like the town’s railway forefathers did still continues on in the present day.

At the apex of rail operations in America, there were 3,000 roundhouses that helped keep everything running. But over the course of time and thanks to alternative transportation methods like trucks on highways and planes in the sky, many of those facilities shut down and only stand today as dilapidated relics from a former world. It is estimated that only 200 roundhouses are left standing in the United States, with only one-third of those still in service. Huron’s roundhouse has continued to stand the test of time and in 1998 was admitted to the National Register of Historic Places due to its cultural and historical significance.

“What we all do varies each day. It depends on what we have in the shop. Usually I work outside power. Other days, I service the locomotives including fueling, restocking them with supplies, as well as adding oil, sand, or water,” said Tapken.

“Other guys work inspection. That’s where they check over the locomotives and fix any issues found. We will be starting to rebuild locomotives here shortly so that will be a lot of work. Changing engines, wheels, the traction motors, and anything else you could think of we do. It’s hard work, but it’s fun, too. Our goal is to always be up and running. There are a lot of people depending on us to get the job done.”

The future in Huron, as with railroads across the country, is not clear. There is no doubt that railroads will continue to play a major role with respect to the nation’s economy. Yet industry leaders are in agreement that technological advancements, such as automation, will have a profound impact on the industry. This translates to fewer rail jobs for the next generation of John Tapkens. Yet experts agree new technologies to modernize our railways are critical to their future success.

Ian Jeffries, president and CEO of the Association of American Railroads, is confident that the future of rail appears to be as bright as it has ever been. Not only that, but he believes the industry will be at the forefront of developments that have a positive effect on the nation’s environmental stability as the rail system moves away from fossil fuels toward cleaner power.

With a strong push at the national level to reduce fuel consumption, many have advocated a drastic transformation of the industry toward full rail electrification. Currently, less than 1% of the United States’ rail system is electrified — a daunting figure, when you consider that electricity supplies more than a third of the energy that powers trains globally. In the coming years, the debate on the future of trains and the potential for widespread electrification will amplify.

In addition to potential advancements surrounding freight operations, there are many advocates calling for a drastic upgrade for America’s passenger rail system. Over the past several years, there has been a significant increase in people using trains as a preferred method of transportation. In 2019 alone, more than 32.5 million individuals used Amtrak, which was an all-time high for the nation’s longtime leader in passenger train transportation.

With train travel at the highest rate it’s ever been, visionaries are stepping up to the plate with ideas to help meet that demand. Recently, the US High Speed Rail Association released its 5-Point High Speed Rail Plan, which focuses in-depth on the nation’s investing heavily on high-speed passenger rails that can connect the country. Advocates are hopeful that in the coming years such proposals will become a reality, considering the country is far behind places like Japan, China, and Europe, which have been streamlining their production for decades.

While the future of trains and railways in the United States is still unclear, their presence in history is cemented. The railway is illustrative of the hope and prosperity and emblematic of the ingenuity and hardworking nature of the American spirit and will continue to be for generations to come.

“I’m not so sure about the future,” Tapken said, standing outside the roundhouse in Huron. “Everyone here is just focusing on the present. Truth be told, the past years have been some of the most productive and busy we have had that I’ve ever seen.”

Tapken expects to see alternative-energy and electric trains, along with automation doing more and more work, but for now, he said, “We’ll keep working hard like our railway predecessors did, and when the time comes to adjust, we will be there to lead the way like we always have.”

Read Next:

Comments