As a member of the Army’s elite 75th Ranger Regiment, Marty Skovlund Jr. completed five combat deployments. But the only time he ever got shot was in basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. It was a hot July afternoon on the range, and as he waited for their targets to get marked, he felt what seemed like a nasty bee sting on his right shoulder.

“I pulled my top up, and there’s a perfect little hole there,” Skovlund said. “I’m like, ‘That’s not from a bug!’”

To this day, Skovlund is not sure how he got shot. He was told it might have been from a fellow private on an adjacent range not following protocol, but that was never confirmed. The bullet entered next to his armpit and missed his spine and an artery by a millimeter.

“If you nick that, shit goes sideways real quick,” Skovlund explained.

But his drill sergeant thought fast. “He just kneads it out like he was kneading bread,” Skovlund said. “Like if you had a marble under a piece of uncooked pizza crust, and you had to just smooth the crust out until the marble popped out on the other side, that’s essentially what happened. And then he gave it to me like, ‘Here, you can show this to your grandkids one day.’”

Skovlund said the story might make it into a memoir of “all the funny/tragic shit that happened to me over the course of my military career.”

The creator and executive editor of Coffee or Die Magazine, Skovlund is also an award-winning filmmaker and author of multiple books.

“I hope that I can be a speakerphone for the guys and gals on the ground and what they feel, what they see, what they’re thinking,” Skovlund said. “I feel like if more people were giving people who feel like they’re not heard a microphone, then maybe things would be a little bit better than they are right now.”

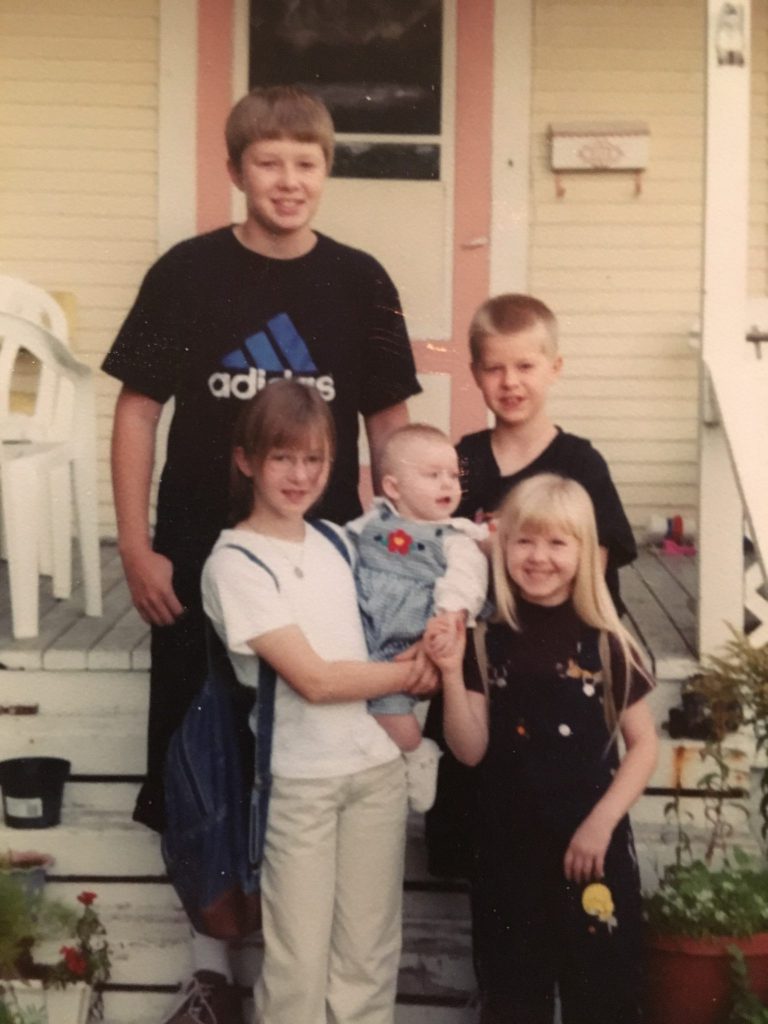

Skovlund grew up in Huron, South Dakota, as the oldest of five children. His father worked as a mechanic on the Dakota, Minnesota, and Eastern railroads, and some of Skovlund’s earliest memories are of taking him lunch at the roundhouse. His mother was working on her bachelor’s degree for much of his childhood and used to take him along to class. He had a very conservative Christian upbringing.

As the family income didn’t stretch very far, Skovlund started working at a young age. Even at 8 years old, he was “going around knocking on doors after a blizzard to see if I could scoop your walk for 10 bucks, or in the summer seeing if I could mow your lawn for 15 bucks. Just literally pushing my lawn mower from house to house.”

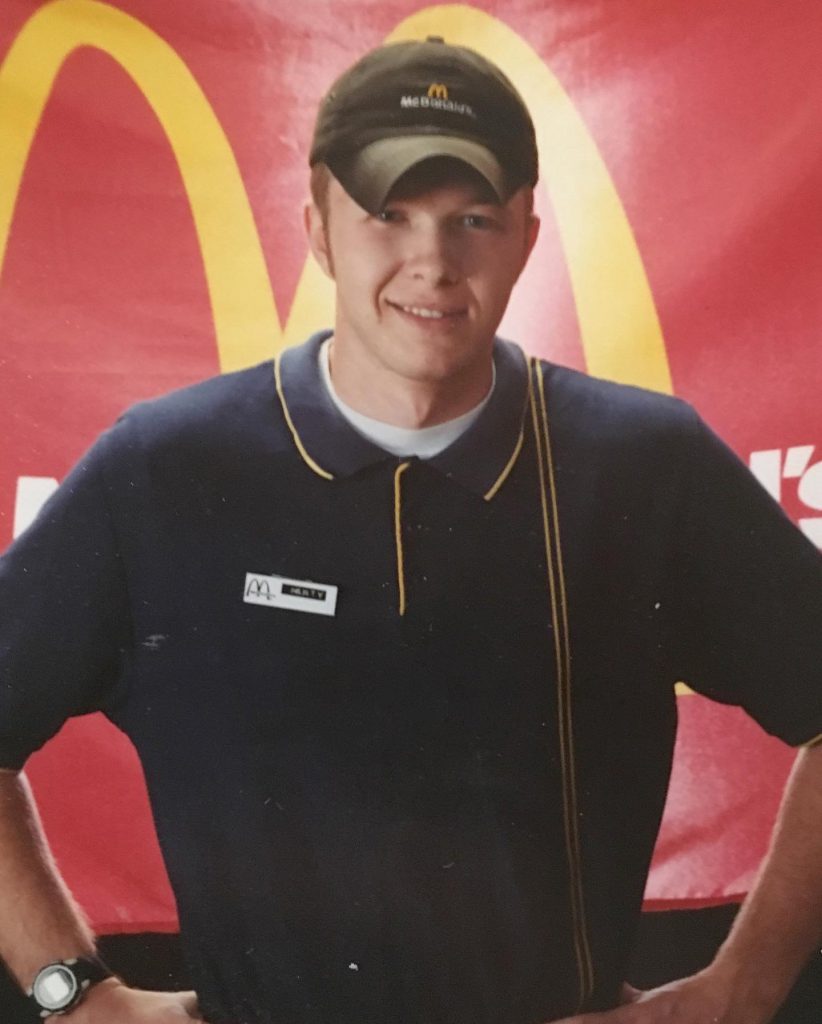

As soon as it was legal for him to get a job when he turned 14, he got hired as a waiter at the local hotel and convention center. For a while he also worked at McDonald’s, and later had a short stint as a telemarketer for Cellular One. But he had two true career goals in life: either he would be an Army Ranger or he would play basketball for the Los Angeles Lakers.

As a backup plan, he considered becoming a history teacher.

“If professional basketball wasn’t in the cards or being one of the most elite soldiers in the world wasn’t in the cards, here was something I felt reasonably confident I could accomplish if it came down to it,” Skovlund said.

He loved to debate from a young age, even participating in his mother’s college classes.

“I was very outspoken, so I would get into arguments with the professor about whatever topic they were covering,” Skovlund said. “I’m sure I came off like this super arrogant little kid, but I do think if I were to look back on those arguments, they would hold up.”

In high school he joined the speech and debate club, which influenced his approach to journalism.

“You know your topic going into a debate, but you don’t know whether you’re going to be the pro or the con, so you have to prepare arguments for both sides,” Skovlund said.

As a journalist, he prides himself on avoiding bias when he can and said he’s “constantly cross-examining my own thought process.”

In high school, Skovlund spent his free time hiking, kayaking, and fishing, as well as running cross-country. He planned to hike the Appalachian Trail the summer after high school, but when he realized he was not going to be the next Shaquille O’Neal, he listened to the Army recruiter who told him he would have to leave immediately following graduation if he wanted a Ranger contract.

“I learned later in life that was a big lie,” Skovlund said, laughing. He graduated on a Sunday and left for basic training on a Tuesday.

He got a chance to experience his postgraduate summer when he was forced to take a 30-day convalescent leave from basic.

“The news had already made it around my small town that I got shot,” he said, “so I basically came home as the equivalent of a war hero and had probably about the most epic 30 days that a 19-year-old can have.”

After recovering and returning to finish basic training where he had left off, he headed to Airborne school, where he promptly got food poisoning.

“So I ended up throwing up in the sawdust pit, got recycled, and had to wait a week to get started with the next Airborne class,” Skovlund said of the second health-related interruption in his burgeoning military career.

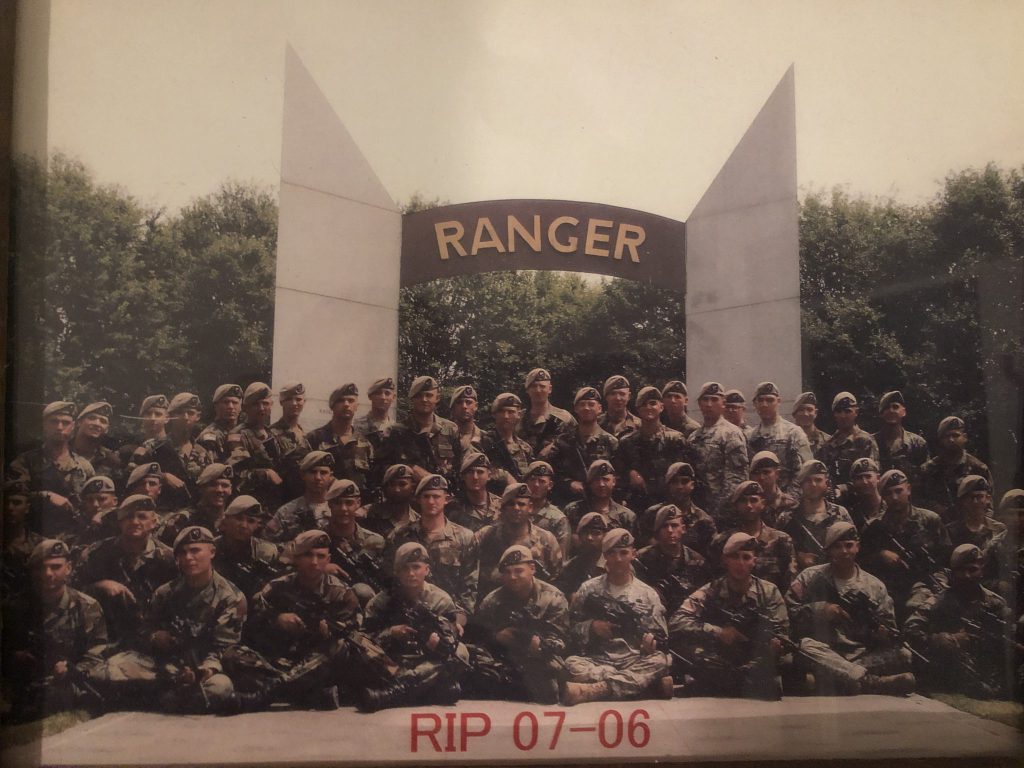

His next step was waiting to start what was then called the Ranger Indoctrination Program, or RIP, the selection process for the 75th Ranger Regiment.

“That’s completely game changing,” Skovlund said. “We are not playing the same fucking game — this is real shit.”

He had never known the background of his drill sergeants or Airborne instructors, but the cadre at RIP “are all straight-up steely-eyed killers, with multiple special operations deployments under their belts, who openly talk about shooting people in the face like it’s just like making a cup of coffee in the morning.”

He made it through RIP on his first try, but not without yet another disastrous incident that threatened to derail his plans. Two days before getting his tan beret and scroll, Skovlund fell off the fast rope tower after the guy ahead of him got the rope caught in his canteen. “Right as I reached out for the rope, he took the rope with him,” Skovlund said. With only one hand on the rope, Skovlund began to slide. “You start to burn through your gloves,” he said, “so you just instinctively let go when your hand starts to feel like it’s on fire.”

In true Ranger fashion, he received very little sympathy for what would end up being fractures to his ribs and tibia and was told that if he didn’t get back up and do the rope again, he would have to recycle back to day one.

“So I kinda hobbled my way up there and did this half-assed fast rope down, all broken up,” he said.

He graduated on time, but unlike his basic training injury, he headed off to 1st Battalion straight away.

“Didn’t realize until later that maybe I should have just taken the restart and then shown up to Ranger Battalion fully healthy,” Skovlund said. “Now I was kinda showing up as this broke dick.”

In the meantime, his run of bad luck continued. His first week in Battalion, he cut off a fellow Ranger’s finger.

“I would maintain that it was not exclusively my fault,” he said. While driving a Stryker infantry carrier vehicle, “the dude on the winch had his finger too close to the actual winch gear, and so when I winched in it sucked his finger in and lopped it off.”

Skovlund had a moment of real panic. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, I just cut this dude’s fucking trigger finger off, his career’s over, he doesn’t have his finger anymore!’” The Ranger eventually returned to full duty, although he had to learn to shoot differently.

It was a rough start, but two months later — on the Fourth of July — he headed off on his first deployment to Iraq.

Skovlund never thought of himself as an all-star, especially not on his first deployment.

“I got the shit smoked out of me every day,” he said. “I didn’t get anybody killed or anything like that, but nobody was bragging about me either by any stretch of the imagination. I was never much more than a mediocre Ranger, on a good day.” He measured his life in training cycles and deployments, three months away and six months home. In total, he completed five deployments — three to Iraq and two to Afghanistan. On his fourth deployment, he finally found a niche to fill.

“I think my problem was that I overthought everything,” Skovlund said. “My platoon sergeant at the time really gave me a chance. He identified that something that required a little bit of overthinking would suit me better.” So he was assigned to augment the platoon’s technical surveillance operator. “That introduced me to this whole new world of special operations that was based around signals intelligence.”

Moving forward in that field would have required a new selection course, and that became his new goal. But instead of doing that right away, he did something no Ranger is expected to do — he dropped a packet to become a recruiter. He had gotten married between his fourth and fifth deployments, and when his wife, Lauren, graduated from the Savannah College of Art and Design, he felt an obligation to let her burgeoning interior design career take the lead for once.

The hope was that he would be assigned to a location near her family in the Northeast.

“I’m pretty good at talking to people, I can sell the shit out of stuff — I could probably kill it as a recruiter,” Skovlund rationalized. “That gives Lauren a couple years to be back home near her family, and then I’ll switch my MOS to be a crypto-linguist. But the Army did its Army thing, and instead of letting me go to Boston, they stuck me in Auburn, New York, which is NOT Boston.”

It was also definitively not a place to try and start an interior design firm in the midst of the 2009 recession, so their plan quickly went off course.

But Skovlund pulled his weight as a recruiter, bragging that he even recruited 18 people who eventually made it into the 75th Ranger Regiment during his tenure.

“As far as regaling kids with cool guy stories, I had a few,” he said of his success.

While working that job and still preparing to become a crypto-linguist — he “crushed” the Defense Language Aptitude Battery — he also wrote a short story called “The Ranger” about a recurring memory from his fourth deployment. It went viral throughout the military community online and totally changed the trajectory of his career.

“People were like, ‘Can you put this stuff on some T-shirts or on a poster or something?’ It started turning into what has become the stereotypical bro-vet business,” he said. “That did so well in its beginning stages that I was like, ‘Man, I feel bad if I just leave this on the table.’”

So at the last second, Skovlund abandoned his plans to move to Monterey, California, and go to language school. Instead, in August 2012, he started his own company, Blackside Concepts. Drawn to the idea of mountain air and planning to be closer to his business partners, Leo Jenkins and Charlie Faint, Skovlund and Lauren headed to Colorado Springs.

The team at Blackside Concepts created two company-affiliated blogs, a satirical site called Hit the Woodline and a serious site for articles and essays about the veteran experience called The Havok Journal. Skovlund quickly realized he liked writing much more than the actual business of selling T-shirts.

“He was really tinkering with the business model, making it more of a media thing and less of a merchandise thing,” Jenkins said.

The business put a strain on his personal life from every angle. After leaving the Army, his family no longer had health insurance, so Skovlund was buying insulin and test strips for his diabetic wife on his credit cards. His house in New York didn’t sell right when they moved, so he was juggling rent and a mortgage while working 18-hour days.

“All of a sudden the marriage isn’t going so hot,” he said. “I’m just not passionate about what I’m doing anymore. I like this writing stuff, but the rest of this is for the fucking birds.” And then he found out his wife was unexpectedly pregnant.

“This all kind of culminates with this ‘come to Jesus’ moment,” Skovlund said, “where my wife and I sit down and say, ‘This isn’t working, so let’s figure out a way to make it work.’ Calling it what it was instead of trying to pretend it wasn’t happening.”

One night in 2015, Skovlund and Lauren were sitting in their daughter’s room, and Skovlund happened to show his wife a picture of a Teardrop camper.

“I said to him, wouldn’t that be nice if we could just be on the road?” Lauren said. “Wouldn’t it be nice to just drive, not be in an apartment, not have all the money in-the-door-out-the-door going to bills?” Skovlund jumped up in excitement, asking her if she was serious. She was.

They made the decision to leave the business behind and move into a van to travel the country. “If we can’t make it work when there’s no room to stomp off to, then we ain’t gonna make it work, that’s our sign,” Skovlund said, explaining his logic. “But if we can make it work in a van, then we can survive anything.”

At this point Skovlund had published a book, Violence of Action, telling the stories of Rangers who served in the Global War on Terror, as well as made two short films, Nomadic Veterans and Prisoner of War, that won awards at film festivals. So when he and his wife loaded up the van and set off across the US, he began to hone his storytelling skills writing for different journalistic outlets while they traveled.

They drove from campsite to campsite, staying at national parks or on land set aside by farmers specifically for campers. Lauren remembers her favorite day of the trip well, driving off the highway on the border of Colorado and Utah.

“It was like the Wild West,” she said. “We went through Rocky Mountain plains, past massive rock formations, leading to an overlook of a canyon with juniper trees. It smelled amazing.”

The canyon was red and orange, with the calm and quiet periodically pierced by the sound of a train traveling along the river. The two watched their dog and their daughter run around all day long. The unconventional choice of living arrangements was a total success.

“That van trip transformed our lives,” Skovlund said. “We saw the country, we got to know each other in a different way, and we had forged our marriage in steel.”

They planned to travel all 50 states, including driving to Alaska and then flying to Hawaii. But the trip came to an abrupt end after 10 months.

Skovlund was in San Francisco in the summer of 2016 when he found out his father was dying of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The van immediately made a beeline back to South Dakota.

Skovlund’s parents were young when he was born — his mother was 18 and his father was 20 — so he had never expected to lose one of them while he was in his 30s.

“I kinda figured I was going to be on Social Security by the time my parents died,” Skovlund said. “I’m going to be 60, and they’re going to be 80.”

After relocating back to Huron, he committed himself to journalism. He wrote regularly for Task & Purpose, worked on a documentary series on the History Channel, and made a big splash with his investigative reporting from the Standing Rock pipeline protests. But all the while, he was living two blocks away from the house where he grew up, watching the devastating effects of ALS on his father firsthand.

Not only was Skovlund witnessing his father’s swift decline, he and his family were grappling with the realization that ALS was carving a swath of destruction through their entire genetic line. Skovlund’s aunt died from ALS shortly before his father was diagnosed. His grandmother and great-grandmother had also both died from it. Next his uncle and his father’s cousin were diagnosed with it. Researchers began interviewing his family. Their experience is unprecedented.

“We’ve got this cloud hanging over us, me and my generation of siblings and cousins,” Skovlund said. “Who’s gonna draw the short straw first? ALS is a real son of a bitch.”

Amid all of this, Skovlund’s sister Molly joined the Army. “She was going off to do this thing that made [our dad] really proud,” Skovlund recalled, “but he wasn’t going to make it through the time she was at basic training.”

The day the recruiter came to pick her up — a routine Skovlund had carried out many times as a recruiter — the family could hear their father wailing inside as they said their final goodbyes. ALS had robbed him of the ability to speak well, leaving him unable to verbalize his feelings for his youngest daughter as she left to serve her country. He knew he was saying goodbye to his youngest daughter for the last time.

Shortly after, Skovlund went to Los Angeles for a reporting assignment, spending two weeks covering the production of SEAL Team, a new show on CBS at the time. After returning home, he found his father already unconscious and on his deathbed. He had missed his chance to talk to him one last time by only six hours. The family began taking shifts, watching and waiting.

“I remember so viscerally, that night after I found out that he was never waking up again, I had this thing come over me where it felt like there was something physically being ripped out of me,” Skovlund said. “I was crying uncontrollably, really could not control the heaving. It felt like something I was connected to was being ripped apart. There’s something we don’t understand about souls departing that became so clear to me at that time.”

Skovlund was by his father’s side two days later when his brother, a paramedic, called time of death at 3:49 a.m. on Aug. 6, 2017. The brothers zipped up the body bag together, Skovlund brushing a lock of hair from his father’s forehead. Marty Skovlund Sr. was 52 years old.

After his father passed away, Skovlund moved to New Hampshire, near his wife’s family. Shortly thereafter, he and a friend he’d known for a few years began kicking around the idea for a new media venture.

Skovlund first met Evan Hafer at the Shooting, Hunting, Outdoor Trade Show, better known as SHOT Show, in 2014. At the time, Skovlund was trying to secure funding for his short film, and Hafer’s entrepreneurial instincts set him on the right path.

“On the spot he told me exactly what to do,” Skovlund recalled. “Literally within half an hour of meeting the guy for the first time. So I was kind of an Evan fan right from the get-go.”

Over the next few years, Hafer and Skovlund kept in touch, with Skovlund doing some freelance writing for Hafer’s new company, Black Rifle Coffee Company.

“The business finally grew to a point where they were looking at some different media plays,” Skovlund said. He and Hafer discussed starting a whole new media company, but it wasn’t financially feasible. Then Hafer suggested Skovlund could run BRCC’s blog, but Skovlund wasn’t sold on that idea.

“I was doing no-shit serious journalism and making a name for myself,” he said. “I’d run a blog; I’d checked that box.”

So instead Skovlund pitched his idea for a free-standing online magazine for the company that would publish serious journalistic pieces about a variety of topics surrounding the military, first responder, and veteran communities. Around the same time, in early 2018, he was given the opportunity to return to Afghanistan to embed with a Special Forces team.

“I was like, ‘I don’t know if you want to hire me or not, or if you want to go forward with this thing, but I’ve got a great opportunity to launch it on. If we’re going to do this, let’s fucking do it,” he said.

In June 2018, Coffee or Die Magazine published its first issue. Skovlund’s piece about his trip to Afghanistan, “The Valley Boys: How a Lone Special Operations Team Is Fighting ISIS in the Remote Mountains of Afghanistan,” was the first big feature the online magazine published. He had taken a trip there about six months earlier to write a piece for Task & Purpose, but his second trip was a different experience altogether.

“That was the first time I had been shot at in a really long time,” Skovlund said.

It was a slightly odd feeling, being back in a war zone in a totally different context.

“I was going back to a lot of these places I’d already been as a soldier, like Bagram and J-bad,” he said. “You feel like, ‘Hey, I’m one of the boys!’ But you’re not— you’re a journalist. And they know that, and you kind of have to be real with yourself.”

However, the team he embedded with was very welcoming. They knew he was a former Ranger and trusted him to know his way around a tactical environment. He tried to keep a low profile.

“I certainly didn’t want to get myself injured and then be the liability for them,” he said. “Now their mission’s ruined because Skovlund got shot or something. Which at this point I’m very aware of my track record, right? It would have been very Skovlund-esque of me to get shot and ruin somebody else’s day.”

Skovlund returned unscathed and with material for both the written piece and accompanying videos.

“I was trying to be a one-man wrecking crew as far as a media team goes, and produce something just as good as what those Nat Geo guys could do.” Skovlund said with a laugh, “There’s a little bit of a chip on my shoulder, like, I can go out and play with the big boys by myself.”

Skovlund took on a heavy load, acting as executive editor of Coffee or Die Magazine while also perpetually traveling to do more reporting. He went to Normandy for the 75th anniversary of D-Day, to Munich for Oktoberfest, and to Maryland for a glimpse of the crazy life of motocross superstar and all-around daredevil Travis Pastrana. But the story that he would later be most proud of was his profile of Senior Chief Petty Officer Shannon Kent.

Kent was a Navy cryptologist attached to a Joint Special Operations Command team who died in a suicide bombing in Syria in 2019 while hunting for an ISIS cell. While writing that story, Skovlund became deeply intrigued by Kent’s multifaceted life.

“The more you peel the onion back, the more you’re like, ‘Holy shit, where did they find her?’” Skovlund said. “Cancer survivor, marathon runner, mom, wife, warrior, special operator — at the HIGHEST LEVEL special operator — seven languages, master’s degree AND bachelor’s degree done WHILE serving as a special operator WHILE raising kids WHILE maintaining a marriage. I remember thinking at the time, This is a book, not an article.”

So Skovlund and Kent’s husband, Joe, pitched a book based on the article and got a contract with William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins. They are aiming for a publication date sometime in 2021.

“I was apprehensive about working with a regular author or standard journalist,” Joe Kent said. “I couldn’t see myself comfortably doing this and opening up my life to anybody else but Marty. I don’t think there’s anybody else out there doing what he’s doing right now. For me it was a no-brainer.”

Former business partner Leo Jenkins agreed with that assessment.

“I think he’s the kind of person who wants the best of whatever it is — whether it’s a film or an article, whatever the best story is, he wants it to come out,” Jenkins said. “He’ll step back when it’s not his time to shine, and he’ll take the reins to move something forward. There’s not a lot of ego in that guy.”

“Writing is a very personal endeavor,” Skovlund said. “A lot of time is spent in a room with the door closed battling your innermost thoughts. I think some people think of that as the romantic part of being a writer. No man, that’s the shitty part of being a writer. The fun part is getting to go out on assignment and travel and talk to people. The shitty part is sitting in your room by yourself just trying to take your insecurities head on and having the courage to turn that work in and show it to somebody else.”

While he balances his editorial duties at Coffee or Die Magazine with his work on the Shannon Kent book, Skovlund has seen his life’s purpose coalesce. In the end, it’s very simple: “There are a lot of people who do a lot of selfless stuff in this country. I want to spend my life telling their stories.”

This content originally appeared on coffeeordie.com.

Read Next: Meeting God: The Powerful Psychedelic Therapy That Could Help Heal Our Wounded Vets

Comments