When Christopher Miner Spencer died in January 1922 after 88 years of life, he’d accomplished quite a lot. The inventor had filed multiple patents over his long career for a number of firearms, among other things. He even produced some of the earliest steam-powered automobiles. Still, one could argue that his most impressive accomplishment, by far, was how he went about securing a military contract for his Spencer rifle.

He simply walked into the White House with one of his guns and sold it to the president. That took balls, even in the 1860s — or perhaps, especially in the 1860s.

Luckily for Spencer, the president’s security detail was still building toward its penultimate failure of the 19th century, and so he proceeded unaccosted and headed straight into President Abraham Lincoln’s office in August 1863 with what would become the Spencer repeating rifle. In an ironic twist of fate, John Wilkes Booth was in possession of two Spencer carbines when he was killed in April 1865.

After working in machine shops for silk mills and locomotive factories, Spencer cut his teeth in firearms design at the best place possible at the time: Colt’s factory in Hartford, Connecticut. The job undoubtedly jump-started Spencer’s gun designing career, but he was interested in guns even as a young boy. His grandfather was actually a gunsmith and a veteran of the American Revolution.

While the Spencer rifle didn’t have the rate of fire offered by the lever-action repeaters that would follow it, it was a reliable rifle that was, nonetheless, a repeater with seven-round capacity at a time when most rifles were muzzleloaders or single-shot breechloaders. The gun’s tubular magazine was located in the stock. Cycling the rifle required the user to work the lever-action to eject a case and chamber a round, but this didn’t cock the hammer. That had to be done manually in an additional step before the gun could be fired, hence the slower rate of fire.

The Henry repeating rifle was also introduced in 1860 with a lever-action design that would soon become the standard for repeating rifles and a much higher ammo capacity. But Spencer’s design was more robust, and because it was a mostly sealed design, it was far more resistant to combat conditions and grime than the Henry.

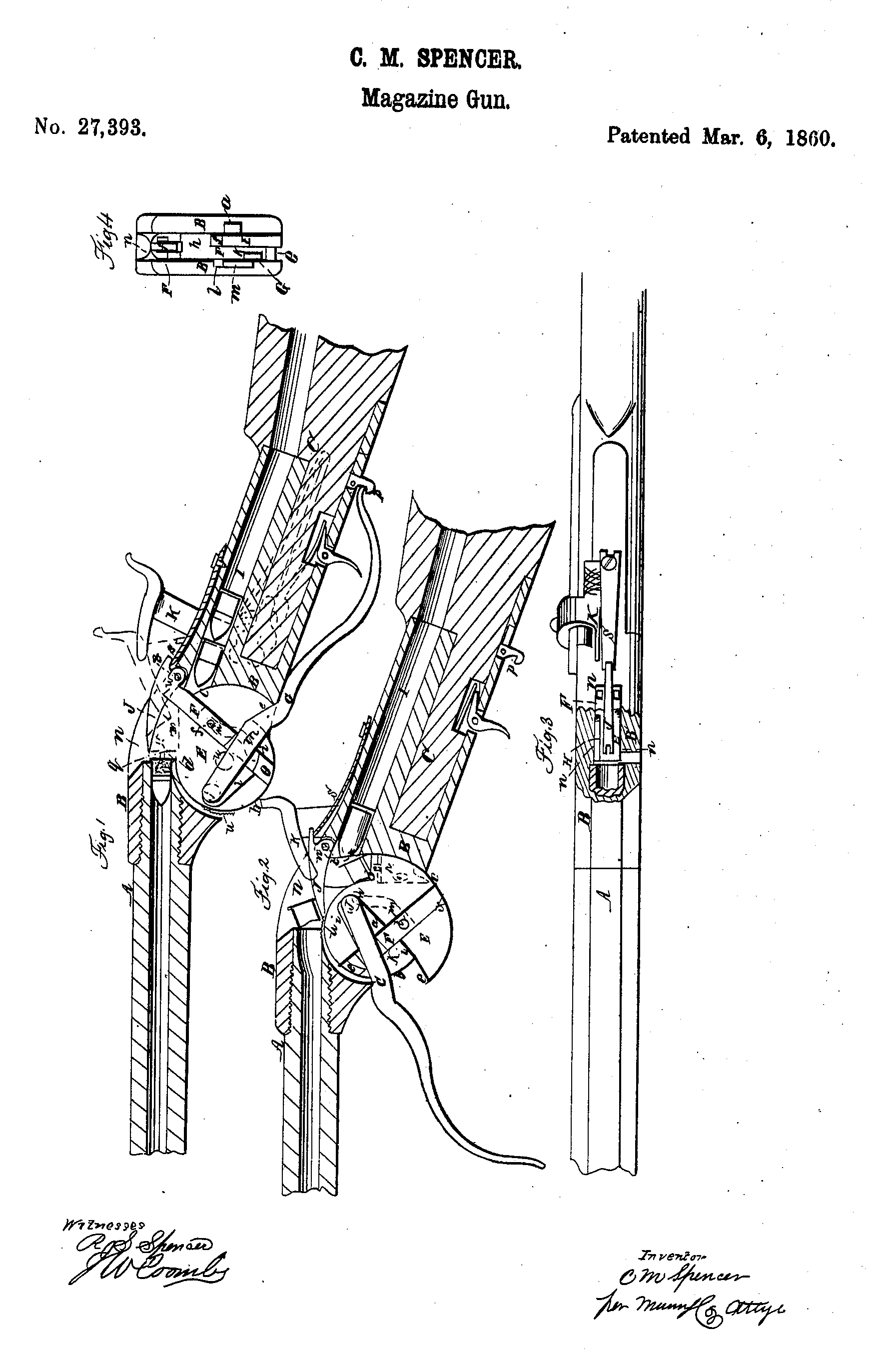

By 1860, Spencer had secured a patent for his seven-shot repeating rifle that used recently developed metallic cartridges. With the American Civil War on the horizon, the timing for his design should have been perfect and could have turned the tide of the war sooner, but bureaucratic red tape hampered him at every turn. That and the fact that his rifle cost far more to produce per unit than a Springfield Model 1861 rifled musket.

Spencer’s connections with Navy Yard Commander John Dahlgren, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, and Ulysses S. Grant enabled him to secure a government contract with the Navy not long after the war began in 1861 — but the order was for just 700 rifles. (The 13th Pennsylvania Reserves were armed with spencer rifles from this lot at the Battle of Gettysburg.)

The real roadblock to the rifle’s military acceptance was the War Department’s Chief of Ordnance Gen. James Ripley, who was very much entrenched in the old way of doing things. The guy was born when George Washington was still president, and he graduated from West Point in 1814 during the reign of the flintlock. As such, Ripley regarded all repeaters as “newfangled gimcracks.”

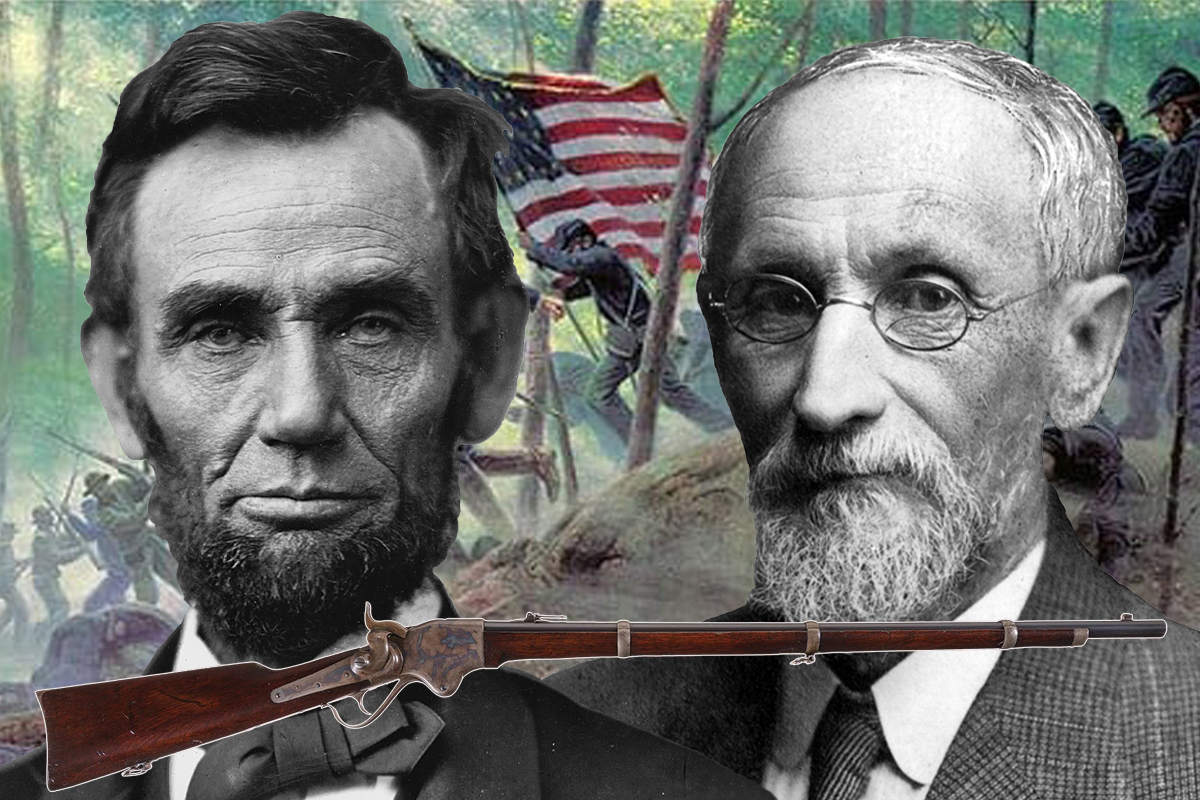

Stymied by one stubborn officer, by 1863, shortly after Gettysburg, Spencer had had enough. He went over Ripley’s head in a truly grandiose way by marching right into the president’s office to show Lincoln why the Union Army needed his new gun — uninvited and unannounced.

Once he got in and somehow didn’t get shot or thrown out onto Pennsylvania Avenue, Spencer disassembled and reassembled the gun for Lincoln, who had requested to see “the inwardness of the thing.” Lincoln must have been impressed; he invited Spencer back for a live-fire demonstration the following day.

The next afternoon, Spencer showed up on the National Mall with his newfangled gimcrack of a rifle for some range time with the president near the uncompleted Washington Monument.

The target was a board about 3 feet long and 6 inches wide. It was placed at a distance of 40 yards, and Lincoln shot one end of the board. It was then flipped for Spencer to shoot the other end.

John Hay, Lincoln’s personal secretary, accompanied the shooting party and recorded an account of the events shortly thereafter:

“This evening and yesterday evening an hour was spent by the President in shooting with Spencer’s new repeating rifle. A wonderful gun, loading with absolutely contemptible simplicity and ease with seven balls & firing the whole readily & deliberately in less than half a minute. The President made some pretty good shots. Spencer the inventor a quiet little Yankee who sold himself in relentless slavery to his idea for six weary years before it was perfect, did some splendid shooting.”

When they were done shooting, the board was cut in half, and Spencer kept the portion that Lincoln shot as a keepsake.

Impressed with the repeater, the president attempted to remove the red tape. He ordered Ripley to adopt the Spencer rifle, but the stubborn West Pointer refused, and Lincoln removed him as head of the Ordnance Department later that year.

This opened the door to a considerably larger military contract for Spencer and his rifle. By the end of the war in 1865, more than 100,000 Spencer repeating rifles had been made. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough to keep the company afloat, and Spencer went bankrupt anyway.

He sold the company’s assets to the short-lived Fogarty Repeating Arms Company. In 1869, Oliver Winchester acquired that company’s remaining assets and brought them into the fold of his recently-renamed Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

At this point, Spencer was employed at Sylvester Roper’s arms company. He had developed a repeating shotgun around the same time, but it, too, proved unsuccessful, and the company soon went belly-up.

Undeterred by the failure of both his and Roper’s companies, Spencer continued to think up new inventions and tinker around with various gun designs. By 1882, he had formed another arms company and produced a five-shot slide-action shotgun that he designed. There was also a (very) short-lived military contract for a paltry 600 guns.

By 1890, his business was unsustainable, and Spencer sold his patent rights to Francis Bannerman, who is today known as the “Godfather of Milsurp.” He made Spencer’s guns with his own markings until 1907.

That was about it for Christopher Spencer in the firearms world. He had to watch Oliver Winchester and Bannerman achieve success in the arms industry while being forced to sell his assets and patents, and it must have sucked. While he didn’t get the recognition he deserved in his lifetime, Spencer’s designs are well-regarded today for their ingenuity and have earned well-deserved places in the timeline of gun history and the repeating rifle, as well as the safes of many gun collectors. He was just a lousy businessman.

While he never established a titanic gun company, a patent Spencer held for a machine to automate the manufacturing of screws provided him with enough money to eventually retire from the day-to-day grind and focus on tinkering with gun designs and other concepts that interested him, including those steam-powered cars. Around 1904, he made 10 steam cars for a New York dairy, powered by burning kerosene. That’s some forward-thinking.

Even in his old age, Spencer kept busy. The 1920 census lists him as an employed engineer at the age of 86, and he was working right up to his death on Jan. 14, 1922.

Editor’s Note: This post has been updated to reflect that the president’s office, in Lincoln’s day, was not yet the modern Oval Office in the West Wing of the White House.

READ NEXT – The Unceremonious Death of Samuel Colt

Comments